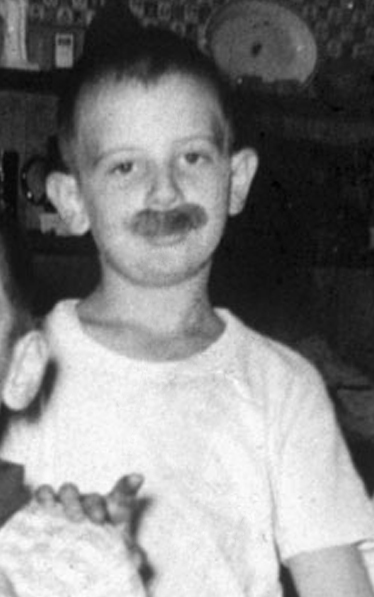

I find some relief in there being no photo of me in blackface. Even if such an image popped up these many decades later, I was 12 years old then and not the governor of Virginia.

Lost from that Halloween of 1963 is who among three grade-school pals suggested it would be fun to shade our faces with burnt cork to trick-or-treat as poor black kids. Regardless, the candy haul met expectations, and no one in our small-town county seat in northern Illinois objected to the costuming.

Concepts like cultural appropriation and white privilege certainly weren’t on the local agenda as the national civil-rights movement warmed toward a full boil. Neither were Halloween warnings to college students about costumes being insensitive if not demeaning and racist. Rare in 1963 would be the white person not exposed to blackface in media or live entertainment while laughing, applauding or ignoring it in mindless acceptance. That it was a racist power play was lost on us but not on others who saw it corrupting even black entertainers.

The black-face Comedian had its origin in the dark days following slavery. The Georgia minstrels, Alabama blossoms and other companies, so deeply impressed the idea upon the minds of both races, that now a black face must have white rings around their eyes and mouth to appear upon the stage. This is not only practicsed (sic) by professional theatrical people, but the horror of it, that is practiced by local dramatic clubs, staged for the race only. – Rucker Smith, “The Black Face Comedian has Done Equally as Much Harm to the American Negro as the Race Hating Play, “Birth of a Nation,” The Kansas City (Mo.) Sun, Dec. 25, 1920.

No black families lived in our rock-ribbed Republican community built on farming, industry and the jobs and courts of county government. Our minority was the Catholics, once a main target of the Ku Klux Klan even in our county two or so decades earlier. Only after my industrialist grandfather was gone did I learn he stood up for a Catholic physician in the early 1950s by muscling the bank into approving a loan for what became a successful medical practice.

A black couple lived across the river, he coming into town to do yard work, she working in the Catholic school cafeteria. Occasionally a black or brown kid, the child of a railroad track worker, breezed through our grade school staying only until a Burlington Route locomotive pulled the string of boxcar housing down the line to the next job site. We heard what is now ever so politely called the N-word kicked around more by older boys, and other than the racist version of the nursery rhyme “Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo,” it didn’t surface at home.

In the canonical Eeny Meeny, “tiger” is standard in the second line, but this is a relatively recent revision. If it doesn’t seem to make sense, even in the gibberish Eeny Meeny world, that you’d grab a carnivorous cat’s toe and expect the tiger to do the hollering, remember that in both England and America, children until recently said “Catch a nigger by the toe.”— Adrienne Raphel, Paris Review, April 16, 2015.

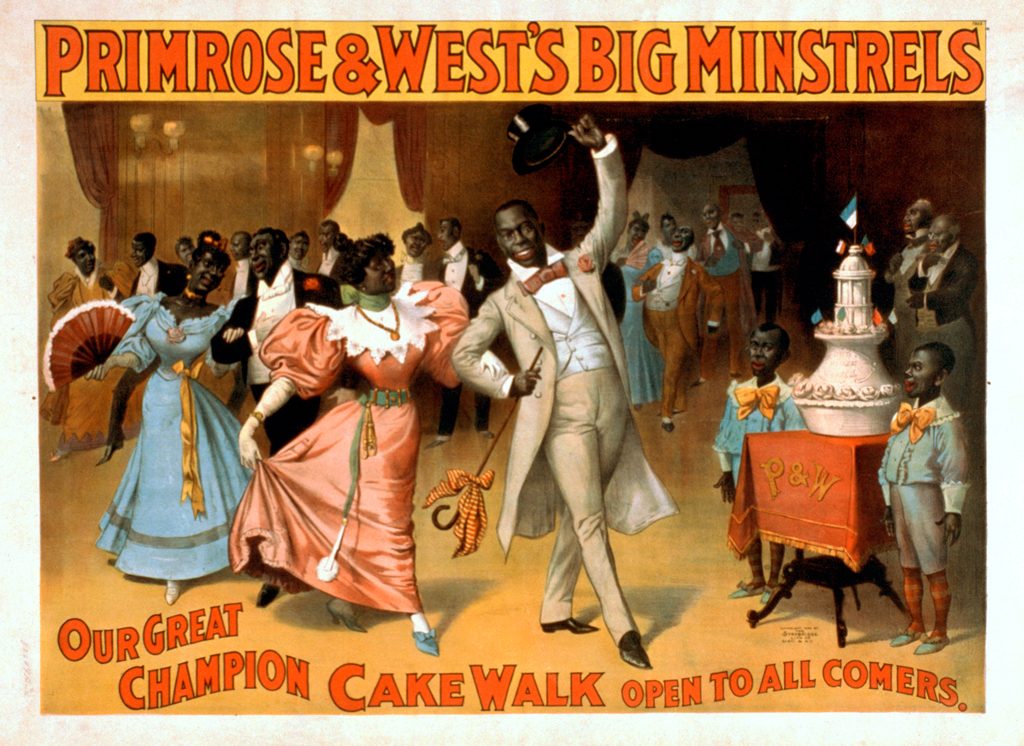

What the town did showcase was an annual minstrel show, the amateur version of the multitude of professional stage and traveling musical, dance and comedy productions springing from the pre-Civil War south. Blackface entertainment proved immensely popular and enduring among white folks around the country. An 1830s minstrel character, a white man blackfaced as the happy slave Jim Crow, lent his name to the legal separation of races by law under the transparent pretense of equality. The early minstrel song “Zip Coon” added to derogatory names for blacks.

Minstrel shows became so pervasive even some black performers joined putting blackface on black face. For entertainers it was a job and potential step up to something better.

It seems to be a vanishing institution, not that its popularity has waned, but because a burnt-cork genius isn’t permitted to work long as a minstrel end-man. Vaudeville and big musical shows grab him. – Unknown writer reminiscing in the Freeport Journal-Standard, Freeport, Ill., Sept. 14, 1922.

Towns of any real or alleged talent and import from Maine to territorial Hawaii got up their own minstrel shows with names like “Roll Dem Bones” usually to fund the good works of some civic group, church or school featuring “burnt-cork artists.” The Rotary Club sponsored ours needing two performances on consecutive nights to accommodate demand in 1953. A newspaper review of those shows suggests my father, a teacher and former big-band singer, performed in a blackface quartet dolled up in “yellow suits with black stripes, white gloves, loud socks and beautifully colored bows under their chins.”

Mayor La Guardia and former Governor Alfred E. Smith will appear together in blackface on May 26 for the first time in their public careers, it was revealed yesterday. Their debut as a blackface comedy team will be made at an amateur minstrel show to be given at the St. James Theater by New York Lodge 1 of the Elks, of which Supreme Court Justice Ferdinand Pecora is exalted ruler. – New York Times, March 8, 1935.

New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Smith, the 1928 Democratic candidate for president smeared for being Catholic, apparently thought better of the idea appearing instead in formal tailcoats. New York Times coverage of the event described the justice and two other state judges as “a trio whose judicial dignity was completely effaced by burnt cork and red silk pantaloons.”

I have no specific memory of our hometown show although with Dad as the high school drama teacher complete with makeup materials, we kids cobbled together costumes and glued on mustaches at home. Beyond Jefferson Street, the big media of the time found plenty of ways to disgust black people and influence white children: cartoon portrayals of Africans and African-Americans in Bugs Bunny and Popeye and other animated relics from the 1930s-’40s abundant on 1950’s and early ’60s television; the white-for-black radio and movie characters Amos ‘n’ Andy created 100 miles east in Chicago; and the slow-walking, slow-talking, stereotypes populating Saturday matinees. So pick one or all, but trick-or-treating as a black child didn’t spring from nowhere.

America sometimes resembles, at least from the point of view of a black man, an exceedingly monotonous minstrel show; the same dances, same music, same jokes. One has done (or been) the show so long that one can do it in one’s own sleep. – James Baldwin in The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings, Randall Kenan ed., Pantheon Books, New York, 2010.

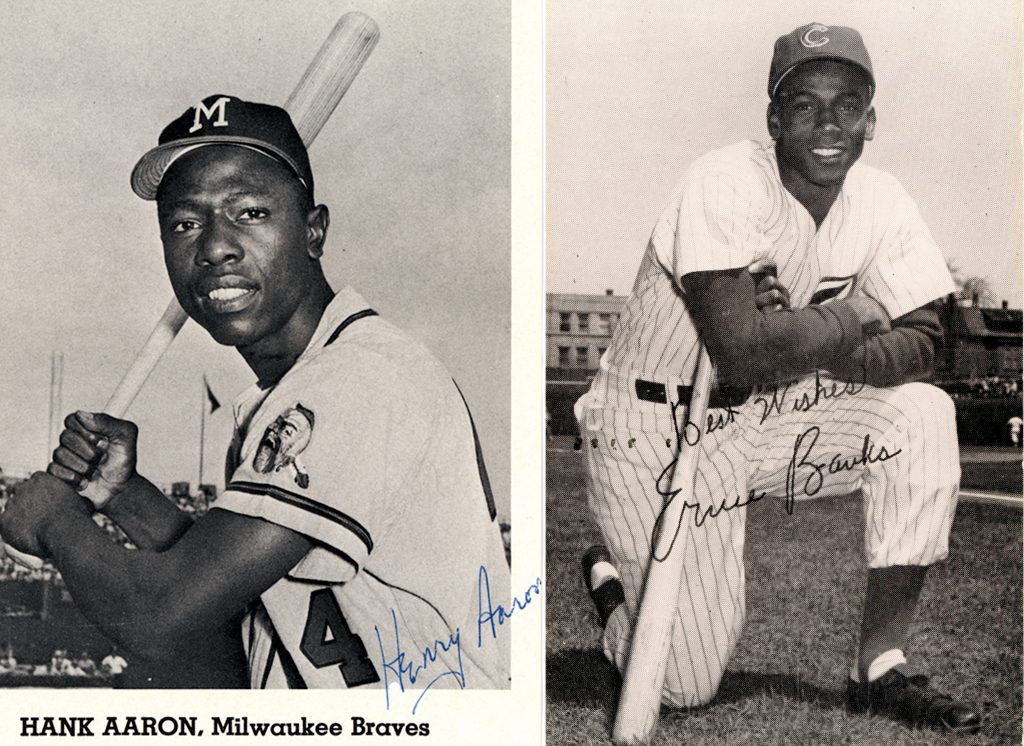

But life was changing even if a 12-year-old didn’t recognize the increments. For one, the integration of Major League Baseball a few years before my birth made it seem natural for white Little Leaguers to have black sports heroes. Mine were in particular Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks (I wore his No. 14 playing first base as he did) and Billy Williams followed not far behind by the Giants’ Willie Mays, Cardinal’s Bob Gibson and Braves’ Hank Aaron, even though he played for the hated Cubs rival in Milwaukee.

I should have known something was up when Dad uncharacteristically took my next younger brother and me to the downtown theater on a school night to see “Lilies of the Field,” the production that made Sidney Poitier the first black actor to win an Academy Award for best actor. The parents, it turned out, were plotting.

Then there was Thelma Carpenter, the no-nonsense and quietly progressive head of the town’s Carnegie library, who steered me and other young readers away from the children’s section. In my case the destination was adult Civil War books like the first volume of Bruce Catton’s new Civil War trilogy published coincident with the centennial of the war over slavery. This leaped beyond typical Illinois grade-school history where Lincoln freed the slaves, the North won, and everything’s been pretty much fine ever since. I am eternally in her debt (and was able to tell her so when I visited the old hometown 30 years later.

The early 1960s were a time when most towns enjoyed a daily paper or two, or in our case a weekly with dailies delivered from Chicago and Dixon about 15 miles down Rock River. For a while mail carrier Toots Farrell delivered the National Observer, a weekly launched in 1962 with correspondents in the South occasionally fleeing nightriders. Our Dumont television brought in one network newscast, NBC’s Huntley-Brinkley Report, which in September 1963 expanded from 15 minutes to half an hour. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been arrested in Birmingham, Ala., that April, and in June an assassin cut down civil-rights leader Medgar Evers in front of his home in Jackson, Miss.

My scrapbook from that year displays astronauts, baseball stars, still-living historical figures like Winston Churchill and Douglas MacArthur and the recently deceased Eleanor Roosevelt and Marilyn Monroe. And there were these clips: Evers’ funeral and a full-page color image of James Meredith, the first black student to receive a degree from Mississippi State University, where an armed guard accompanied him to class. Two years later he would survive being shot from ambush on a remote Mississippi highway during his solo “March Against Fear” from Memphis, Tenn., to Jackson in support of voter registration.

So, despite a racist nursery rhyme, misstepping into blackface and watching the world from a white Northern town comfortable in its 19th century roots, freshly sown seeds were sprouting, as they no doubt were for other white kids. My own brush on the receiving end of prejudice, however, remained a few years in the future.

By Halloween 1964 the family decamped to New Mexico trading omnipresent greenery and mighty Rock River for desiccated desert and the occasionally dry Rio Grande. It wasn’t love at first jolt as angry wind propelled buckshot grit across the hood of the Plymouth wagon as we first entered Las Cruces.

This was to be a one-year family adventure as my father sought another college degree. With three Western schools from which to choose, my mother remembered Las Cruces as a pleasant place from her days as a collegiate tournament golfer at the University of Arizona before World War II. So here we were 40 miles from Mexico with a short time to absorb a strange land.

Only as that year stretched into forever did I learn of the subplot hatched by our parents, he from Pennsylvania’s multi-ethnic coal country and a scat singer in an interracial quartet in the 1930s, she the daughter of privilege bestowed with a generous spirit and love of people. Beyond our little ears they talked through the burgeoning civil rights movement and decided one of the best things they could do for their five sons in a frothing society was to expose us to other cultures even if briefly.

We dropped into a different world where the state constitution protected the Spanish language and the population was on track to being all minorities, we Anglos among them. In this weird place black people, a visible presence but outnumbered 3-1 by Native Americans, were considered white.

I don’t think there was any place with less racial tensions than in New Mexico with people growing up talking a different language. Now let me tell you a little story. In the old La Fonda, there used to be a bar, and there were a couple of real black bartenders. And I remember one evening I was sitting back there having a drink or two too many, and the bartender, this nice black gentleman, why, I said, I don’t think the KKK ever, I don’t think we ever had those problems in New Mexico. He said, ‘You know, us Anglos have to stick together.’ Now, the definition of an Anglo, or a native as we said, was the language, it wasn’t the race. If you initially talked the English language, you were an Anglo, and this is the way it was accepted. If your original language was Spanish, you were a native, or a Spanish-American was the term used. And so I call to your attention here, we’re sitting there at the bar, and this black man says us Anglos have to stick together. OK, you did have in places like Santa Fe, Rio Arriba, we were the minority. – Attorney and former District Court Judge Harry Bigbee (1915-1999), Santa Fe. N.M., interviewed Nov. 13, 1987.

Catholicism infused New Mexico as it had since the first Spanish occupation. On Fridays that guaranteed fish or red cheese enchiladas in our junior high cafeteria. I brought lunch from home until I wised up to New Mexico cuisine and the skill of the women in the kitchen.

Nearly everyone, black kids included, lived on the same side of the Rio Grande and mostly the same side of the Santa Fe Railway tracks. It would be several years before I discovered Washington Elementary School was named not for George but Booker T. and had been the city’s segregated black school until shortly before the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education ended school segregation in another 10 or so New Mexico cities. By the time we arrived, decades of blackface minstrel shows had come to an end.

While a single year would have been eye opening, our time expanded as Dad gave away the snow shovel, signed on with the first faculty of the city’s second high school, and he and Mom played golf year-round. Discoveries kept coming: a Mexican War battle a few miles down the Rio Grande; nearby Mesilla as the Confederate capital of Arizona; Buffalo soldiers battling prejudice and Apache warriors; cross-border bootlegging during Prohibition; the Klan meddling in government and schools; the slow acceptance of Native Americans as full citizens.

Las Cruces had more than doubled in population since World War II after the Army set up White Sands Missile Range. The missile base bused its students to Fred H. Lynn Junior High, which seemed to rival the population of the town we left behind. Lynn stood out as a mash-up of deep-rooted Hispanics, transplants like us and a spectrum from families relocated for the military and civilian space programs. At school Jewish kids didn’t stand out from the Catholics or we Presbyterians although Long Island accents did. That there were neither black students nor teachers speaks to the whims of the principal.

High school accelerated change. A trumpeter in the band adopted a sax man as a project taking me home to his village across the Rio Grande on the Butterfield stagecoach route where his parents welcomed me into their home. As bonuses he introduced me to the struggles of farmworkers (“Is that union lettuce?”), a first-hand hassle by the Border Patrol, and how to eat a plate of beans with a stack of corn tortillas.

This opened a side of our new home present before U.S. troops swooped down the valley during the 1846 invasion of Mexico. Unlike the northern part of the state, where sharp dealings and outright fraud dispossessed Hispanics of their lands, there were few land grants in the inhospitable south to generate perpetual hostilities.

Which is not to say everyone was as generous. I already had enough anxiety when I started dating as I stumbled blindly into new territory and first meetings with wary fathers. I certainly wasn’t prepared for the response from a classmate I’ll rename Angélica when I asked her out for dinner and a movie. “My father doesn’t let me date white boys,” she said with no rancor. We remained friends as happened later in another setting when bridging Catholicism with backslid Presbyterianism didn’t click for long.

The election of Barack Obama in 2008 generated hope of a country turning toward something better more than 400 years after Africans imported in bondage met European immigrants and now 156 years of dealing with slavery’s aftermath. Instead, six days after Halloween 2016, hope took a hit with a successful presidential campaign reliant on bullying rhetoric and social division. Just a setback on a long road, one wants to think, and not a retreat to a past when attacking blacks, Catholics, Native Americans and a succession of immigrant waves yielded political gold while the country paid the price. Now suppressed issues erupt as mass movements attacking sex assault as male privilege, unjustifiable killings of black men and women by law enforcement, denial of voting rights, and blackface as more than harmless amusement.

It gets dark sometimes, but the morning comes. – Jesse Jackson, 1988.

At the moment in Virginia, Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam and Attorney General Mark Herring plus Republican Senate Majority Leader Thomas Norment Jr. resemble political pretzels over blackface. Northam, 59, did or did not appear in a blackface photo in his 1984 medical school yearbook but conceded applying shoe polish to his face several years earlier to be Michael Jackson in a dance contest. Herring, 57, went public with wearing blackface to a college party, and Norment Jr., 72, who initially demanded Northam’s resignation, let it be known he was managing editor of the 1968 yearbook at all-white Virginia Military Institute when the book included racial slurs and blackface photos although, he said, none of him. VMI enrolled its first black cadets that fall.

Black shoe polish is in high demand. – Movie writer-director-producer Spike Lee, quoted in Variety, Feb. 6, 2019.

As these incidents increase, so does the debate over what, if anything, qualifies as atonement for racially insensitive episodes years and decades past that didn’t rise to the level of lynching or bombing churches. Stay tuned as more revelations, denials and apologies surface, as they now will.

If anyone wants to call for the governor’s resignation, they should also call for the resignation of anyone who has supported racist voter suppression or policies that have a disparate impact on communities of color. … In our present moral crisis, we must remember that real repentance is possible — and it looks like working together to build the multiethnic democracy we’ve never yet been. — The Rev. William J. Barber II, How Ralph Northam and others can repent of America’s original sin, Washington Post, Feb. 7, 2019

Draw what you will from the current state of affairs. I offer only this: Reading is fundamental; librarians are rock stars; prejudice rises or dies at home; your neighbors aren’t the enemy; history matters; unresolved social conflicts hold us back; and ignorance is curable. Navigating the story of America challenges everyone, but to be wide awake you accept that even if still playing Little League ball.

Bill,

I so admired your dad. I was on the faculty at OCHS with him and he sang in my choir at 1st Presbyterian Church. I was disappointed when he didn’t return to Oregon after a year in NM. You certainly inherited his knack of erudition. I enjoyed your writing and recollection. Your move to NM opened experiences you would not have had in Oregon, but of course you missed the “Oregon Experiences.” You obviously turned out to be a writer he would be very proud of.

Thank you. I like to think Dad would have approved of these rambling tales I’m telling. We all remember Oregon quite fondly, so a number of things had to line up just right in deciding not to return. We did rent the Illinois house for a second year just in case.

Nice essay, Bill. My only experience with minstrels was watching The Al Jolson story with my brother, Charles — for what seemed like a few hundred times. By the way, didn’t you tell me that members of the Klan were elected to the legislature from the Farmington area?

Mike: I can’t say for sure state Sen. William Butler (D-Bernalillo, Sandoval, San Juan) of Farmington was a member of the KKK. However, at the beginning of the 1925 Legislature, when the Senate ousted him over alleged voting irregularities, an unsigned letter from the Farmington Klan on the letterhead of “San Juan, Klan Number 23, Realm of New Mexico” protesting Butler’s removal became public. The letter also denied Butler was a Klan member although you’d be hard pressed to find any politician touting KKK membership when running for office, and there certainly were more than a few. The 1925 Legislature is the one that rewrote the Education Code to allow segregated black and white schools for the next 29 years.