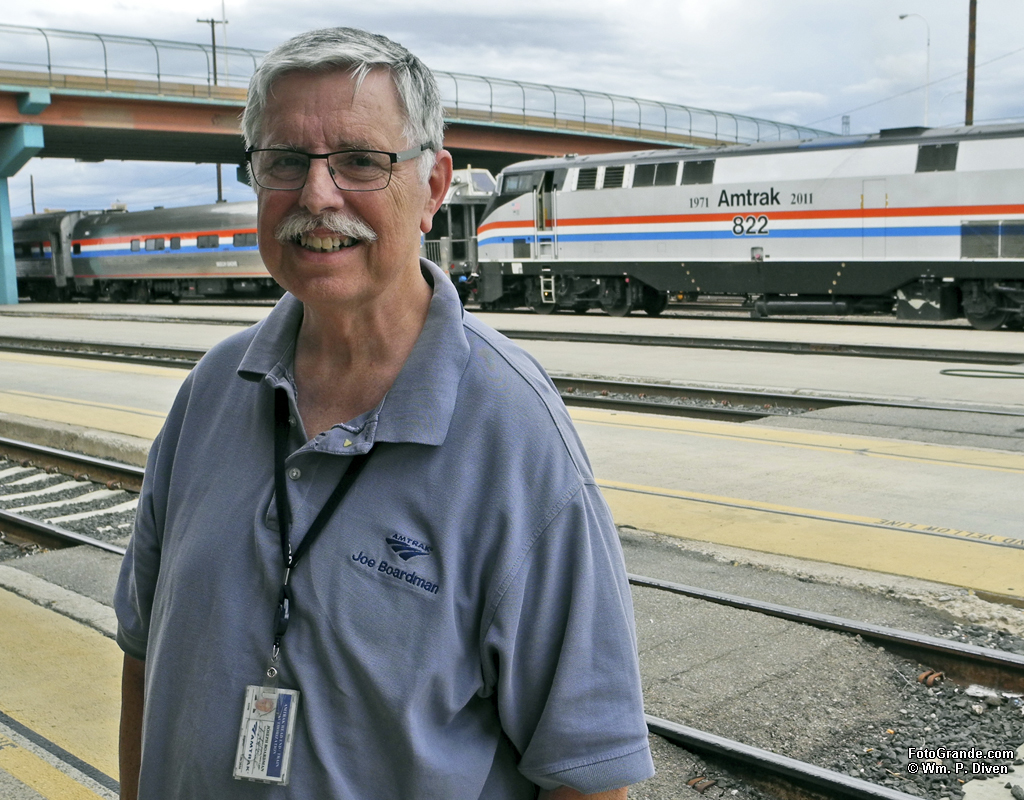

When I bumped into Amtrak President Joe Boardman outside Albuquerque’s faux-adobe station, his wife scanned the trackside vendor tables stocked with jewelry, souvenirs and burritos.

Amtrak President Joe Boardman in Albuquerque, Aug. 5, 2016. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

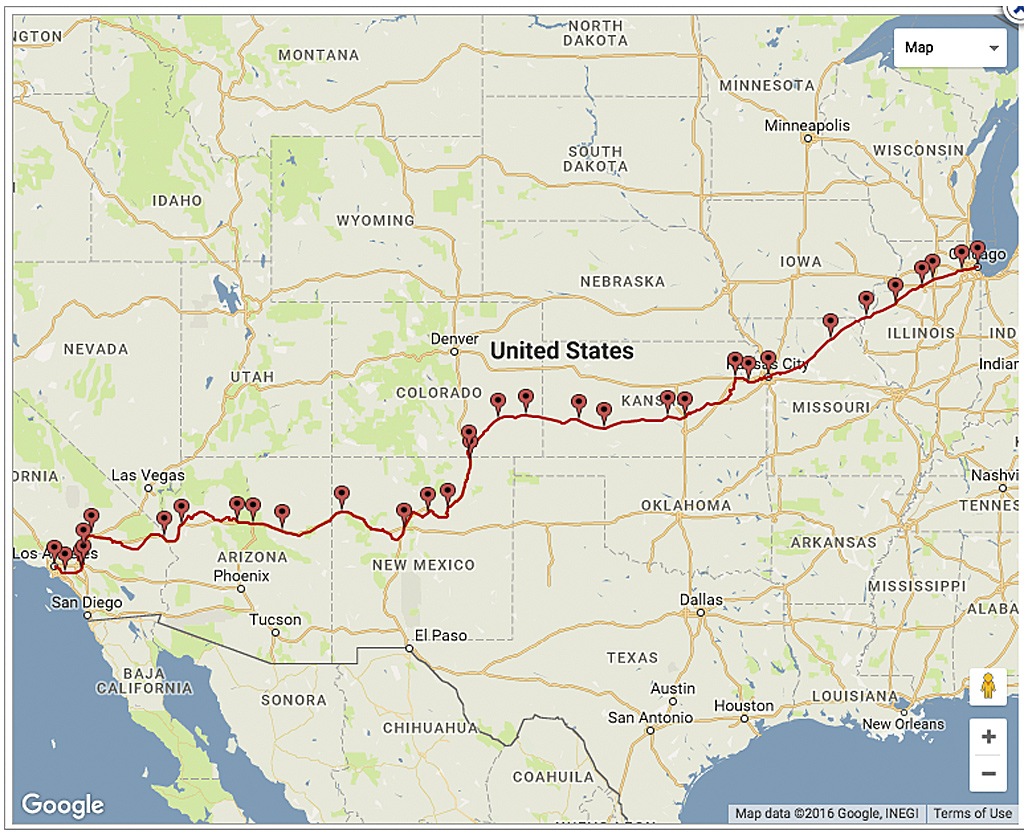

Business is good for those New Mexico entrepreneurs when Trains No. 3 and 4, Amtrak’s Southwest Chief, are on time leaving Lamy, the rural stop for Santa Fe, and Gallup in the red-cliffed Indian Country almost to Arizona. With timetables padded to help maintain the schedule, on time at Lamy and Gallup usually means early into Albuquerque in late morning going east and late afternoon chasing the sunset.

That gives passengers from Chicago, Los Angeles and 31 big and small places in between an hour or so to walk around as the trains take on fuel and change crews. At the moment the only customers are a few would-be Amtrak passengers and a handful of people off Boardman’s special train, and he’s wondering where both of his Southwest Chiefs are. They should have been here by now with one of them already long gone.

Passenger railroading is far removed from pre-Amtrak days when management might wink at exceeding speed limits until some Casey Jones screwed up while picking up stray minutes. Still, there are a few stretches of BNSF Railway track west of Albuquerque into Arizona where Amtrak flies legally at 90 mph.

On the day I met Boardman, it’s a tossup as to which Southwest Chief will arrive first. Meanwhile his special train — two locomotives and five cars — rests over on Track 4 awaiting the next day’s run down the Rio Grande Valley to El Paso, Texas.

Set to retire in a few weeks at the end of August after eight years in charge, Boardman is taking something of a victory lap from New York to the Rio Grande and back inspecting track, proselytizing for passenger trains, maybe relaxing a little and still thinking ahead.

He is enjoying one success from June when the last of 70 electric locomotives built by Siemens for 125 mph took over regular trains on the Washington-Boston Northeast Corridor (NEC). That was nearly $500 million spent to replace engines as old as 36 years.

But he points to his locomotives, General Electric diesel-electric Genesis models painted and lettered for Amtrak’s 40th anniversary in 2011, as one pending issue. Amtrak rosters more than 200 of them ranging in age from 15 to 20 years, and his successor will need to rebuild or replace them, he says.

The NEC Acela fleet, at 150 mph over 35 miles the best the U.S. can muster for high-speed rail, also shows its age, Boardman adds. Most of the 40 power cars, one at each end of the trainsets, were delivered in 2001.

(A few weeks after Boardman departed New Mexico, Amtrak announced a $2 billion order from French manufacturer Alstom for 28 complete Acela trains to be built at plants in New York. The last of the current Acela fleet is to be gone in 2022.)

As the Chiefs draw closer, Albuquerque is busy as New Mexico Rail Runner Express trains tricked out as red-and-yellow roadrunners arrive from their yard for commuters headed north toward Santa Fe and south toward Belen. At the same time, a BNSF Railway engine is switching three privately owned passenger cars from the Millennial Trains Project. Twenty-six millennials from diverse backgrounds have met with Albuquerque’s mayor and will reboard their rolling idea incubator to complete a transcontinental journey to Los Angeles coupled to the rear of the westbound Chief.

Action in Albuquerque, N.M., Aug. 5, 2016 (left to right): Three private cars being positioned to add to the westbound Southwest Chief; Rail Runner Express Train No. 513 backs toward the Albuquerque station for its 4:30 p.m. departure for Belen; Amtrak President Joe Boardman train arrived about 2:30 p.m. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

A broader concern for Amtrak is long-distance trains like the Southwest Chief, which have enemies in Congress and conservative think tanks. The trains tie the country together, Boardman says, and are the only public transit available in places that lost airline and bus service over the years.

That’s one of the arguments heard in northeastern New Mexico where tourists detrain at Lamy and Las Vegas and locals can board for Albuquerque and elsewhere. Thousands of Boy Scouts from across the country pass through Raton each year heading for the Philmont Scout Ranch.

During Boardman’s 10-day excursion he visited with rail advocates, civic leaders and railroad royalty his train picked up along the way. From Kansas into southeastern Colorado he traveled with BNSF Executive Chairman Matt Rose, whose ancient and underused track nearly killed the Chief.

“The Southwest Chief is safe,” Boardman tells me. It’s a message he’s delivering along the way while thanking governments, groups and civilians for rallying in support of the train.

The dramatic mini-series “Fate of the Chiefs” unspooled as Amtrak’s long-term contract to operate over BNSF came up for renewal and Rose dug in for a better deal. Saying his few freight trains on the route didn’t justify higher-speed track, he threatened to cut maintenance unless somebody else ponied up for the extra work.

That would have meant a speed limit of 30 mph for Amtrak adding several hours to the lope across vast and largely empty high prairie. Amtrak in turn played hardball with Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico as it has done in other states that help fund regional passenger trains.

The public uprising channeled through Garden City, Kan., and La Junta, Colo., which won competitive federal transportation grants in 2014 and 2015. Combined with BNSF, Amtrak, state and local money, they raised $46 million, enough to install 94 miles of continuous welded rail replacing “stick track,” 40-foot rails bolted together, some predating World War II.

The city of Lamar, Colo., is leading a third grant effort seeking $30 million plus regional support. New Mexico is on board for the first time pledging $1 million for new ties and ballast under 24 miles of welded rail the state owns. Only Amtrak uses that section between Lamy and Control Point Waldo, junction with the Albuquerque-Santa Fe Rail Runner line.

Boardman called the recent negotiations with BNSF and Rose tough although on one point they agreed. Neither endorsed the chatter about simply shifting the Chiefs from their historic Santa Fe Trail and Raton Pass route to BNSF’s high-volume twin-track freeway from south-central Kansas through Oklahoma and northwest Texas into eastern New Mexico.

BNSF didn’t want the interference, and Amtrak, with Boardman clinging to his tourist and Boy Scout magnet, couldn’t afford Rose’s asking price anyway.

When all works well, passengers have up to an hour to stretch their legs in Albuquerque, N.M. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

Last year Amtrak recouped 91 percent of its operating costs, but the disparity in revenue sources still leaves the long-distance trains at risk in Congress. The critics unable to rub out Amtrak and who actually believe, or at least pretend to believe, the system should and can turn a profit suggest splitting off the lucrative NEC and letting the national trains fend for themselves.

Advocates contend no national rail system makes money and Amtrak should be adding trains and lines. They note the Southwest Chief and the Seattle-Los Angeles Coast Starlight often run full in the summer and that added cars would boost revenue at modest expense.

What certainly isn’t happening soon if at all, Boardman says, is passenger trains between Albuquerque and El Paso, Texas, a service the Santa Fe started in 1881 and terminated in 1968. Boardman’s special made the run only because BNSF held up traffic on the transcontinental freight line and let the train crawl the wrong way on a westbound track through more than two miles of the Belen freight yard.

Reliability and on-time performance remain troublesome although some of that lands on the doorstep of host railroads. In July the Southwest Chief’s on-time arrivals in Chicago and LA dropped below 50 percent bringing down its rolling 12-month average to 71 percent. The delays are due in no small part to track issues between central Kansas and Albuquerque.

After decades of being nickel-and-dimed by Congress, Amtrak picks its battles carefully. And now someone else will lead the charge.

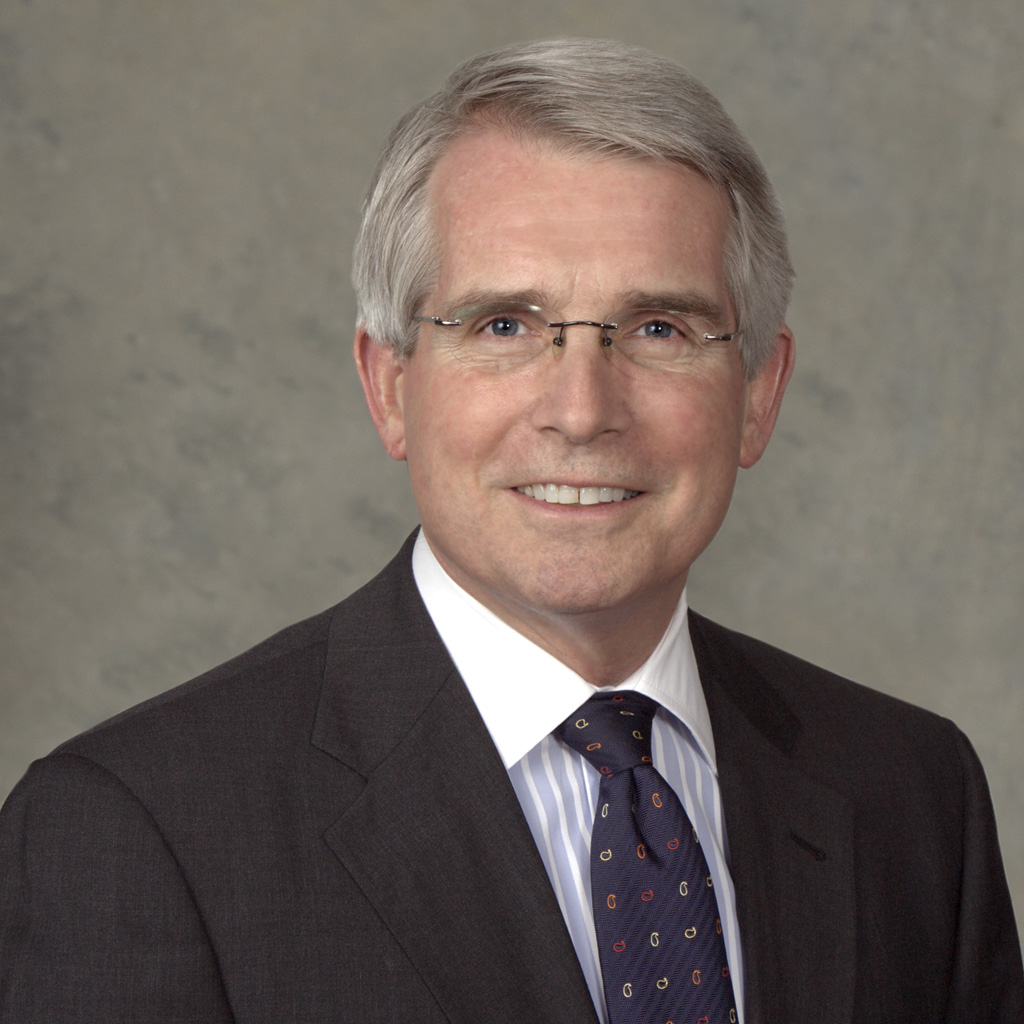

Shortly after Boardman finished his trip, the Amtrak board named as its new exec Charles “Wick” Moorman, the well-known, well-liked executive chairman of the Norfolk Southern Railroad who retired at the end of 2015. Where Boardman’s background is public transit and as head of the Federal Railroad Administration, Moorman rose from the engineering side of private-sector railroads.

“I am really thrilled, and I hope I’m right to be thrilled,” Jim Souby, president Colorado Rail Passenger Association (ColoRail), which fought mightily to save the Chief, told me while I was collecting comment on Moorman’s appointment for Trains magazine. “I’ve always held Amtrak needed more credibility with the freight railroads, and this is what Mr. Moorman will bring to that organization.

“A lot of people had a lot of problems with Boardman, but here at ColoRail we didn’t. He really championed the train and took us seriously about saving the train.”

* * * * *

Postscript:

Amtrak President Joe Boardman (left) and journalist William P. Diven. Photo © Ernest Robart; used by permission. (Click to enlarge)

During my conversation with Boardman and Brian Gallagher, his director-operations and coordination, I told them I owed them a positive story after my past screeds: Amtrak’s Last Scotch (April 2014) and Amtrak’s Southwest Chief Ripe for Mutiny (July 2014).

So, for the the patently weird experiences of summer 2015 and how Amtrak got it right in 2016, please see my Rambling the West Coast by Rail»

(Clarification: The story has been edited to show Boardman retired at the end of August rather than September.)

Update: Joe Boardman died in March 2019 barely six months after his retirement. He was 70.

Best part of the story: Boardman USED to run Amtrak. He doesn’t any more.

His regime will go down (and I do mean DOWN) as among the worst in the company’s history, with an appallingly bad employee safety record getting worse despite his spending tens of millions of dollars on a failed safety iniitiative. He aso presided over the decline of the long distance network, an increaingly poor reliability record of the company’s diesel locomotive fleet, continuing propaganda about the Northeast Corridor “making money” when it actually hemorrages it, so much so that he saw to it that much-needed repairs and maintenance were back-burnered so he could maintain the fantasy.

You don’t owe Boardman and his hired gun Gallagher anything. You do owe your readers the truth.

A correction to your story: your caption under Wick Moorman’s photo says, “New Amtrak President Charles “Wick” Moorman takes over Oct. 1.”

Wick Moorman took over on September 1. Joe Boardman has already taken his rocking chair and from what information has come out of headquarters, I suspect that many of his close associates at Amtrak will soon be returning to their former crafts…if they had any at Amtrak, that is.

Thanks for the correction.