When her train clattered over the Vermejo River, 12-year-old Martha Betty Putnam stopped briefly at Colfax, N.M., a town boasting two railroads and 100 or more people wishing coal to be big business again. Here she crossed the Dawson Railway, a steel river of coal flowing from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains toward distant copper smelters. The raw beauty of northeast New Mexico — tall timber on her right, infinite range on her left — awed the Illinois girl aboard the Rocky Mountain & Santa Fe Railroad as the steam engine in front chuffed along the Santa Fe Trail toward Cimarron, once the seat of empire. From there staccato exhaust echoed into the Sangres before Martha Betty stepped down at the year-old Cimarroncita Ranch Camp for Girls to spend the summer of 1932.

The predecessor railroad boasted Pacific in its name, envisioned Ute Park a mile beyond the camp as a destination resort, and blasted a tunnel higher up for its next move into the Moreno Valley. With abundant timber, coal and other natural resources ripe for exploitation, boosters in the Cimarron News and Cimarron Citizen in 1911 crowed, “There does not seem to be any way to keep the Cimarron country from becoming the Florida, the southern California, and the Klondike of New Mexico all rolled into one.” Instead the railroad ran short of cash and ambition at Ute Park dashing the steam-driven aspirations of hopeful Taos 40 twisted miles farther west.

Saltpeter Mountain rises to the north of Colfax, N.M. in October 1995. The Rocky Mountain & Santa Fe Railroad approached over the horizon from Raton and crossed the Vermejo River here. Warning signals on the highway mark the former Dawson Railway still following the river to Dawson and York Canyon. Photo © William P. Diven (Click to enlarge)

Now three years after Wall Street crashed, coal still gushed as miners worked six mining districts arrayed across 30 miles of mountain frontage from Dawson to beyond Raton. Output peaked during World War I only to slump as world copper prices collapsed in post-war recessions. Recovery would come, of course, especially for the black diamonds so

The cemetery at Dawson, N.M. Phelps-Dodge provided metal crosses for the hundreds of largely foreign-born miners killed in two major disasters in 1913 and 1923. October 1995. Photo © William P. Diven (Click to enlarge)

essential to home and industry. For now, though, fewer coal cars trundled past Dawson Cemetery filled to bursting with European immigrants and other miners killed by the hundreds in underground disasters.

The Depression following the market crash fell onto an already poor state forever at the mercy of outsiders. Spanish and Mexican colonists worried less about royalty than rain and Comanches while the imperial rush of U.S. dragoons simply replaced one unseen regent with another. Government contracts after the Mexican War infused the state with cash and new corruptions, but only big business, the country’s first modern corporations, delivered game-changing disruption.

“It was a life such as had been seen nowhere else in the United States,” Albuquerque author Erna Fergusson wrote in the 1920s. “Broken bits are left here and there — stately courtesy in remote villages, remnants of old morality plays, soft-toned Spanish speech — they too will soon pass. What happened to it all? The blast of a steam whistle.”

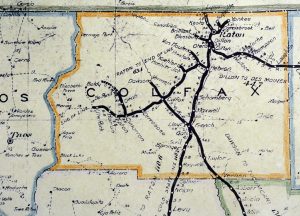

This 1924 map produced for the New Mexico State Corporation Commission shows the final extent of coal and other railroads in Colfax County. The only surviving line, now the BNSF Railway, enters from Colorado on the north running south through Raton, French and Levy toward Albuquerque. (Click to enlarge)

From their Cimarron mansion, mountain man and Kit Carson pal Lucien Maxwell and his wife, Maria de la Luz Maxwell, commanded the 1.7-million-acre Beaubien-Miranda land grant awarded to Lucien’s father-in-law and public and hidden partners. By the time Lucien purchased all the shares in the Mexican-era grant, he and Luz ranked among the largest private landowners in U.S. history overseeing territory roughly 70 miles from north to south by 60 miles east to west. When they sold out in 1870, the fledgling Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Rail Road Company had laid its first track in Kansas heading to New Mexico, Old Mexico

Coal bound for Wisconsin descends the Colorado side of Raton Pass on the Santa Fe Railway. The view is from the rear of the train where a second set of locomotives help with shoving up the pass and braking on the descent. October 1995. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

and California. Business syndicates quickly turned the Maxwells’ domain into foreign and domestic stock plays and development schemes with coal becoming a notable success. Dawson counted 6,000 residents by 1920, and promoters touted 200 years of coal reserves deeper in the Sangres.

Beneath the glowing forecasts loomed more disruption as Martha Betty, the girl who would become my mother, arrived for her memorable summer of 1932. Soon Santa Fe Railway passengers paying extra fare skimmed the prairie 20 miles from Cimarron in the streamlined glory of Super Chief, the latest petroleum-fed speedster needing neither coal nor armies of boilermakers and pipefitters. As bloody madness spread across the world into the 1940s, the War Production Board yanked up most of the rail from Raton to Ute Park for the war effort. Residents grudging but patriotic accepted the loss with some expecting when peace returned so would their railroad.

Dawson barely outlasted World War II devolving into abandoned spoils and bare foundations while mines closer to Raton limped through the 1950s. A final 15-year burst pushed track up the canyon beyond Dawson to dispense coal from York Canyon to a California steel mill and Wisconsin power plant. Those 400 jobs slipped away as strip mining withered and dangerous geology ended underground digging before another disaster made headlines. By 2002 only reclamation remained.

A Santa Fe Railway engine crawls around the balloon track at York Canyon Mine slowly pulling hoppers through the loadout in the background. December 1995. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

Decades earlier the plums of Maxwell’s empire fell to the wealthy — among them Oklahoma oilman Waite Phillips, Chicago grain speculator William Bartlett and later media mogul Ted Turner — who preferred private playgrounds to rapacious resource development. Phillips called his estate Philmont, the name still gracing the property he gave the Boy Scouts of America for their wilderness ranch. Pennzoil acquired Bartlett’s Vermejo Park Ranch and deeded 150 square miles of the Sangres including the Valle Vidal to the U.S. Forest Service. Turner bought the remaining 588,000 acres minus the mineral rights in 1996 selling off the cattle in favor of a wildlife-centered guest ranch populated by natural-gas wells.

The U.S. coal industry may appear strong in the 21st century loading more than four million rail cars last year with an uptick in early 2017. Among other unflinching realities, however, that’s 20 percent fewer carloads than 2015. National production at 40-year lows matches the early 1920s when 860,000 men did what 50,000 mechanized miners do today. When Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt in June touted 50,000 new coal-sector jobs since late 2016, he overlooked a relevant fact. Most of those were support jobs in oil and gas production, which is considered a mining activity. There’s renewed talk of “clean coal” after decades of failed effort at finding a cost-effective method made even more difficult now by the abundance of relatively clean, relatively cheap natural gas.

Coal’s once-dominant share of electricity generation is down to 30 percent of the national market pressured by natural gas and the renewable sources lining up to disrupt the petroleum industry some day. In New Mexico only Peabody Energy, fresh from bankruptcy, still loads main-line coal trains as fewer than 200 employees near Grants in Cibola County produce more than the entire state did in 1918.

The only sign of life in this section of Colfax County these days is an isolated saloon known as Cold Beer, N.M. October 1995. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

The Cimarron country remains a peaceful and great place, and thousands of Boy Scouts headed for Philmont still detrain in Raton only to board buses at the Amtrak station. But the town of Colfax is dead and gone with only an all-alone saloon a mile down the road to mourn its passing. You can just as easily find the town site on Google Maps by typing “Cold Beer, NM” as by searching its name. And the railroad Martha Betty remembers fondly 85 years later? It vanished, too, save a cindered scar still healing in the scrubland of dreams gone by.

Great essay – a welcome addition to what little has been written on railroading in NE NM. Is the NMCC map available online? I’d like to take a look at Union, Harding, and Quay as well. Thanks.

I don’t know if the map is online but don’t think so after some quick searching. It’s roughly 3×4 feet so may exist in that or other form at the successor N.M. Public Regulation Commission or in the state archives or state history museum collection. I’m working off a blueprint copy with my pencil coloring of the county boundaries. No surprises in Union, Harding and Quay. The Dawson Railway, the then-ATSF line from Des Moines to Raton and the CRI&P line east from Tucumcari are the only now-abandoned lines shown.

Thanks BIll. I’ve had a passing curiosity with the Dawson branch as well as the lines that radiated from Raton. Among many other things, I’m always on the lookout for detailed maps and fragments of their stories. David Myrick’s book has a handy map of the area, but I’d like to find one or more with a little more detail.

Hi Jeff:

Can’t say I’ve seen any highly detailed maps of Raton-Dawson-et. al. although the NMSCC map is good in that it lists pretty much every station of that era. Modern topo maps show old grades but not all of them.

Lots of technical information online from old NM Bureau of Mines analyses to newer remediation plans although they’re short on railroad data. There’s also a book out there “The Last Train to Leave Cimarron, New Mexico” by Ronald E. Bromley that I bought online. Good stories, but the maps are rudimentary and hand-drawn.

I’ve uploaded a couple images from my blueprint copy of the 1924 SCC map that you can download. The details a little fuzzy in the original; doesn’t help that I’m shooting up at it from the floor.

https://fotogrande.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NE-NM-1924-NMSCC.jpg

https://fotogrande.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NE-NM-1924-NMSCC-Colfax.jpg