Railroaders operate by a minutely detailed rulebook with one unwritten rule strictly enforced: Late trains get later.

That describes Amtrak on a 2015 roundtrip from Albuquerque to Oregon by way of Los Angeles. But not in this summer of 2016.

Instead two trains covering 2,201 miles on one-way tickets reached both destinations early with only a little fuss along the way. It’s how America’s private passenger rail system operated into the mid 20th century and still does when everything clicks. No ailing equipment, decrepit track, disruptive passengers, dangerous weather or lame dispatching by a host railroad blew up the schedule with hours-late arrivals and missed connections.

Breakfast on the northbound Starlight in 2015 came with a view of Mount Shasta. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

The worst to be said of travels this July is the Coast Starlight café-lounge ran out of Scots whisky before we reached Los Angeles. That’s what I told Amtrak President Joe Boardman when we met trackside in Albuquerque a few weeks later. I also said I owed him a positive story and now had the material to post one.

(For the encounter with Boardman, see my Trainspotting With The Man Who Runs Amtrak. For the rough rides of 2013 and 2014, please see Amtrak’s Last Scotch and Amtrak’s Southwest Chief Ripe For Mutiny. For the even stranger trip on the Southwest Chief last year, read on.)

The Starlight slipped out of Seattle’s King Street Station early on a murky morning in July and 35 hours later pulled into Los Angeles Union Station a little before 9 p.m. ahead of schedule by 13 minutes. In between came picture-window views of Puget Sound and San Francisco and San Pablo bays; the Tacoma Narrows, Columbia River and Carquinez Strait; Mount Rainier, Mount Jefferson and other snow-capped volcanoes (when the weather cooperated), the Cascade and Coast ranges; the agricultural Willamette and Salinas valleys; Pacific cliffs and beaches; and the megalopolises of the Bay Area and Los Angeles.

- See my Coast Starlight photo gallery»

- See also my Olympic Peninsula & Seattle photo gallery»

So no wonder Lonely Planet lists the Coast Starlight as one of its Top 5 scenic train routes in the country. The four long-distance trains to the West Coast via El Paso, Albuquerque, Denver and Glacier National Park provide their own highlights plus the time to savor them.

Amtrak doesn’t promote some sights although they are valuable in their own way. Passenger trains tour America’s backyards and industrial urbanity in all their glory, grit and graffiti. It’s a dose of reality dispensed in jolts that may or may not deepen understanding and compassion.

As is generally the case with the on-board services people, the diner, lounge, coach and sleeper crews on the Starlight and later on the Southwest Chief proved friendly and helpful but also firm when needed. While my fellow travelers presented themselves as peaceful and sober companions, one profane woman with troubles I couldn’t discern was denied boarding in Portland.

“Go home, get a good night’s sleep, and we’ll try again tomorrow,” she was told.

Strangers seated with me in the diner extended my long-term experience of people being conversational, interesting and international (this time Germany and the south of England). That provided not just an inside perspective of the Brexit vote that just happened in the U.K. and an outside view of U.S. domestic politics but more signs we’re part of a global community. As the cliché goes, travel is broadening.

Colored light bathes the art-deco eminence of Union Station seen from the Metro Plaza Hotel. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge.)

The Starlight motors into downtown LA around 9 p.m., about three hours after the Southwest Chief whistles off for Chicago having given up on the connection I only made once in two tries before the schedule change. So Friday night ended at the Metro Plaza Hotel, a 5-minute walk from Union Station past a few people bedding down in the Alameda Street landscaping.

That left most of Saturday for trekking through Chinatown and the old Spanish pueblo around Olvera Street (try the chicken molé enchilada and Cadillac margarita at El Paseo Inn). We slipped out of Union Station at 6:10 p.m. — “on the advertised,” as railroaders would say — and thanks to strategic padding of the schedule rolled into Albuquerque 42 minutes early the next morning.

The Los Angeles-Chicago Southwest Chief also makes a lot of shortlists for best ways to see the country connecting our second- and third-largest cities by way of the Great Plains, daylight crossings of Raton and Glorieta passes and traverses of Native American homelands.

The Southwest Chief follows the Santa Fe Trail down from Raton Pass. Photo © William P. Diven 1995. (Click to enlarge)

Caveats abound, however. Coach fares can compete with airlines but don’t include meals although you do get a reclining seat with real legroom. Despite quiet hours, sleep may be fitful especially if you’re traveling alone and your Starlight seatmate is a fidgety 13-year-old boy you can’t give a hard elbow at 3 a.m. because his mother and brother are sitting behind you with father and sister across the aisle.

Sleeping cars package comfort, seclusion if you want it, meals, bringing your own alcohol and a bed. The 468-mile sleep from Barstow, Calif., to Winslow, Ariz., in July was the best since I rode the Baltimore & Ohio to Pittsburgh at age 12. The downside is Amtrak dings you close to resort-hotel prices.

All was not well on other days this summer, however, as planned track work on the Union Pacific near the California-Oregon state line delayed the Starlight by as much as three hours. Northbound passengers connecting with the Portland-Spokane section of the Seattle-Chicago Empire Builder detrained in Klamath Falls, Ore., for a bus ride up I-5.

And UP still draws negative commentary for its slow freights backing up Amtrak although the complaints are fewer than when Vice President Dick Cheney, a former UP board member, was in office. Then, and occasionally still, the Starlight is known as the Starlate.

On the other hand BNSF Railway, host to the Southwest Chief, draws on its Santa Fe heritage when the Super Chief and other names trains ruled the railroad with even slight delays requiring explanation.

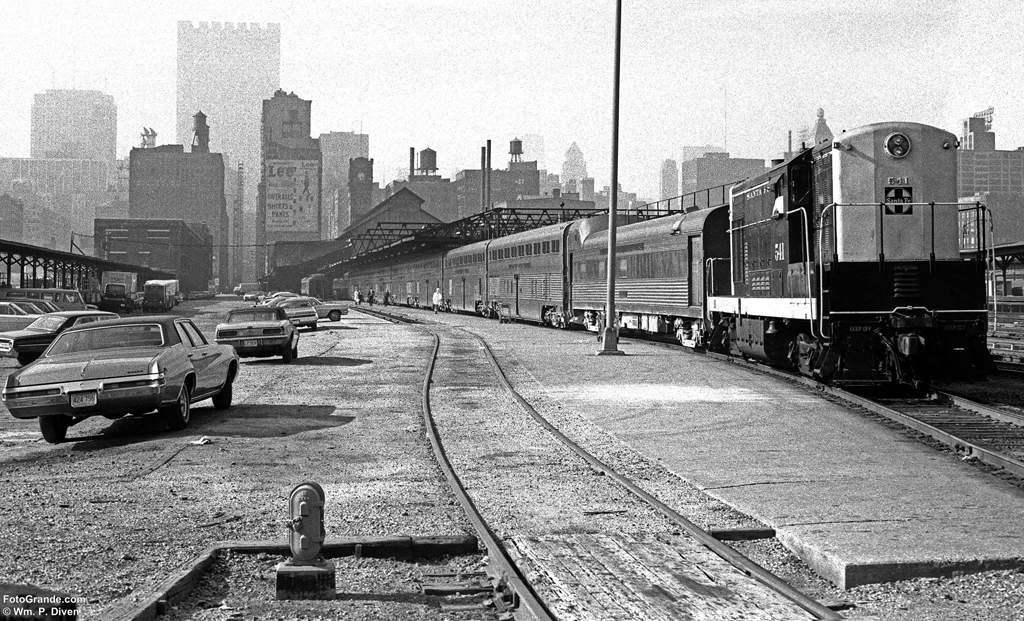

A Santa Fe Railway switch engine shoves the combined Super Chief and El Capitan into Chicago’s Dearborn Station for departure to Los Angeles in 1970. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

Remember that rule about late trains getting later? That was the Southwest Chief going west out of Albuquerque in June 2015.

Various issues — mechanical trouble fixed in Albuquerque, bad track now being replaced in Colorado and Kansas, heat-related speed restrictions, crawling behind a multi-stops commuter train — left us departing in the dark four hours in the hole. By the time I got settled in a Superliner coach, the Chief already had run out of Scotch roughly halfway through its 2,256-mile, 43-hour run to Los Angeles.

Things turned truly weird crossing Laguna Pueblo when the conductor caught a passenger rifling other people’s luggage in the lower level. Fisticuffs ensued, and the man pulled the emergency brake, opened a door and jumped off the moving train.

By the time the crew gave up checking the track for body parts, tribal police arrived and someone said they saw the errant passenger running off into the scrub, we’d lost another hour. I later heard they found the guy’s shirt and shorts but not him.

We made decent time after that and almost made it across Arizona before the engineer and the rest of the operating crew from Albuquerque ran afoul of the hog law, the federal hours-of-service limit of 12 hours. So we stopped short of Kingman until the fresh crew drove out.

A digression on swine:

“Hog law” dates the latter 1800s when trains frequently hit stray swine required by law to be fenced in by the farmer or out by the railroad. An 1873 law limited livestock to 28 hours in transit before being offloaded, fed and watered at a time when railroaders not yet unionized could be worked and overworked at will. Only in 1907 did federal law restrict time on duty to 16 hours. Not surprisingly railroaders call the Hours of Service Act the Hog Law, and one nickname among many for the engineer is “hogger.”

We eventually rumbled into LA five hours late and three hours after the Starlight chortled up the coast. A dozen or so of us boarded the standard lifeboat, an Amfleet road coach otherwise known as an Ambus, for a cruise up Interstate 5 to the commuter station at Bakersfield.

After missing our Amtrak connection in Los Angeles, the substitute bus found Interstate 5 closed by a brush fire. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click to enlarge)

We were somewhere north of Burbank when the driver took a phone call and we saw smoke ahead. A wildfire had just erupted on the Grapevine over Tejón Pass closing I-5 and forcing us into a 112-mile inland detour through Lancaster and Mojave. Even with the extra 60 miles we waited another hour on the parked commuter train that would deposit us in Sacramento where we caught up with the Starlight around midnight.

Despite all that mayhem, Amtrak punched, uh, scanned my tickets and delivered me to Eugene, Ore., fulfilling our contract. We were 17 minutes late.

Mr. Diven:

I have a variety of experiences with Amtrak, like you. I am a regular on the Northeast Corridor (NEC to you) on both regular trains and the Acela from time to time. I go back and forth between Baltimore and Stamford Connecticut every week. I have taken sleeper cars from NYC to Portland twice, took a wonderful trip on the Crescent to New Orleans and back, and, in 1996, took an Amtrak trip around the country with my son. I have experienced it all.

I am troubled that this country (especially in this transit reliant region) does not recognize the need to prioritize Amtrak’s status on the rails and it’s need for a long overdue upgrade. I find the people who work the rails equally frustrated that they cannot give the best service of all available means (food, drink and comfort) every trip, every day.

I am always dismayed at inconsistencies in travel, accommodations, and on-time delivery, but like you, get to see the sun shine enough to make me want to come back, even though I currently need to.

I look for a day in the future when I can take a trip and not worry when I have to get back to work, or can hop from line to line to see the country from the comfort of my seat.

BTW – the best experience I’ve ever had (now 3 times), is waking up in Montana on the Empire Builder heading East between Libby and West Glacier and see the magnificence of nature that is the northern Rockies near the Continental Divide.

(sorry this ran on so…)