Here’s a story of a forgotten 1960s youth movement, the Vietnam War and how 3,300 of my closest friends and I derailed Dick Nixon’s political machine.

In it Team Nixon plans a pure victory and cheats in a failed attempt to get it. It’s also a reminder of why politics can be a great game, why votes count and why voters, especially younger ones, need to wake up and smell the excitement.

You won’t find this story in the history books although a version of my tale appeared in serial form in the Albuquerque Tribune in 1992. This version is still written for the audience of that time with an updating epilogue at the end.

================================================================

Part I: Confessions of a hippie-type Republican

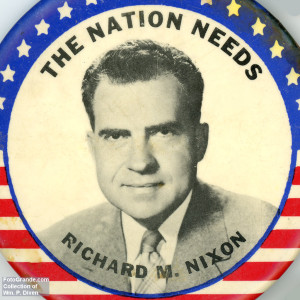

Richard Milhous Nixon glided to victory with a king-pimp strut in that election year of 1972. Unbeatable, unstoppable, hero of his silent majority and undeterred by the malcontent opium eaters ranting in the streets about Vietnam. In August the Republican faithful anxious to anoint The President for a second term marched on Miami Beach like so many moon-eyed cultists chanting “Four More Years, Four More Years…” They knew their leader and soared with the certain knowledge of what was supposed to happen.

Dick Nixon — most of us choking on “The President” adopted the diminutive familiar often using his nickname as a verb — played many roles but never the wimp (see Adult Content below). He drank, cursed, relished football, fought when cornered and climbed to the top without schmoozing for appointive office. No pinko apologist, this World War II veteran built a career brutalizing Communism. Well, yeah, sure, he’d just cozied up to the Red Chinese, but hadn’t the Great Wall photo-op right before the New Hampshire primary buffaloed the Democrats? It certainly stood out as an auspicious start to the Year of the Rat. The far Republican Right screamed bloody treason, of course, but their attempt to steal the presidency fronted by Rep. John Ashbrook of Ohio whimpered away.

No, Dick Nixon might spit in your eye, but he wouldn’t spit up in your lap (like President George H. W. Bush would do to Japan’s prime minister). And few believers questioned Vice President Spiro Agnew’s manhood, integrity or ability to lead if tragedy befell The President. So despite a nagging war, angry conservatives, rumors Agnew accepted kickbacks as governor of Maryland, and that “third-rate burglary attempt” at Democratic headquarters in Washington’s Watergate office complex, Nixon & Co. steered the 1972 campaign full steam ahead with a death grip on the rudder.

But certain re-election against whomever the Democrats picked? Versus pacifist George McGovern, weepy Ed Muskie, rebel George Wallace or “Hubert Who?” Humphrey? Plead no-contest and get outta here. At last everything seemed attainable including a rare and holy gift Republicans last bestowed on Nixon’s then-boss Dwight Eisenhower at the 1956 convention: unanimous first-ballot renomination. Even the detailed nomination-night script climaxed with delegates showering all 1,348 votes on Dick Nixon. Too bad for him a cabal of New Mexicans made sure that deal didn’t go down.

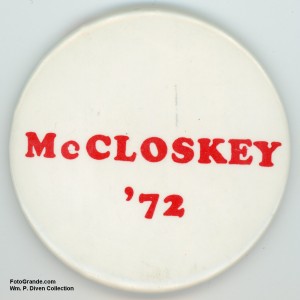

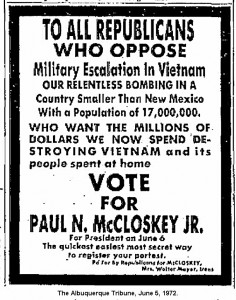

When Nixon’s Horde thundered into Miami Beach, one renegade delegate vote from dusty New Mexico eluded capture, set free in the June primary when a handful of Republicans — from Goldwater holdovers and Rockefeller moderates to peace freaks with eyelids at half-mast — traipsed to the polls and voted for California Rep. Paul N. “Pete” McCloskey Jr. That likely surprised McCloskey as much as Nixon since the congressman abandoned his presidential candidacy months earlier, had no idea he was on the New Mexico ballot and didn’t campaign once he found out. A Republican matriarch in Santa Fe engineered that piece of business, abetted by her son, an occasional professor who covered Vietnam on correspondent credentials from Playboy Magazine. More on them later.

At our cow college near the Mexican border, the anti-war rabble railed against Dick Nixon over bridge games in the student union and 35¢ tostadas compuestas at El Cheapo’s. Few in numbers, we stuck together as much for safety as political bonding. This was New Mexico State University, home of the Aggies, where men, outnumbering women 2-1, specialized in engineering and animal science. Campus cops perched atop the chemistry building to spy on the off-campus coffeehouse, and one administrator sent discrete notes to parents warning of their daughters dating the few black men among our 9,000 students.

Despite the real world, or perhaps because of it, NMSU clung to an impossible innocence. Picture new students wearing red beanies, which, on demand from upperclassmen, they hoisted on upraised thumbs while singing the fight song toward “A” Mountain (“…And when we win this game/We’ll buy a keg of booze/And drink it to the Aggies/Till we wobble in our shoes…”). Each fall upperclass rowdies herded frosh from the dorms to whitewash the A-shaped boulder field laid out by student engineers on the mountain considered sacred by natives of a nearby village. Wags claimed the Aggies someday will learn that letter and replace it with a “B.” We called our then-65-year-old yearbook the Swastika despite Nazis perverting the ancient symbol that still adorns the pre-war federal courthouse in Albuquerque. Complaints of gross insensitivity eventually renamed the yearbook although the fight song stands unmolested, at least until the prohibitionists read this.

By 1972, two barbers in the student union clipped quietly into history as business dwindled away. It wasn’t just men becoming shaggier across the country. Two years earlier university regents dropped the mandatory four-semester ROTC requirement for all men gutting demand for the shorn-sheep look and depriving us of a prime protest target. With ROTC now voluntary, and illicit Mexican produce selling for $60 a pound delivered, the generally peaceful campus with its generally respectful anti-war demonstrations mellowed even more. One noncredit pursuit, cowboys cruising in their pickups for lone hippies to abuse, pretty well disappeared when the Bull Durham set got curious and began rolling their own left-handed cigarettes.

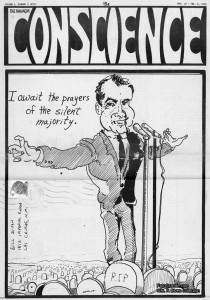

About this time State’s abrasive underground newspaper — The Conscience — succumbed to administration skullduggery leaving the Los Angeles Free Press as our

source of radical news. To buy a Freep, however, meant ducking into the city’s only adult bookstore where an older guy with combative teeth and Katharine Hepburn voice stacked them over the dildo display.

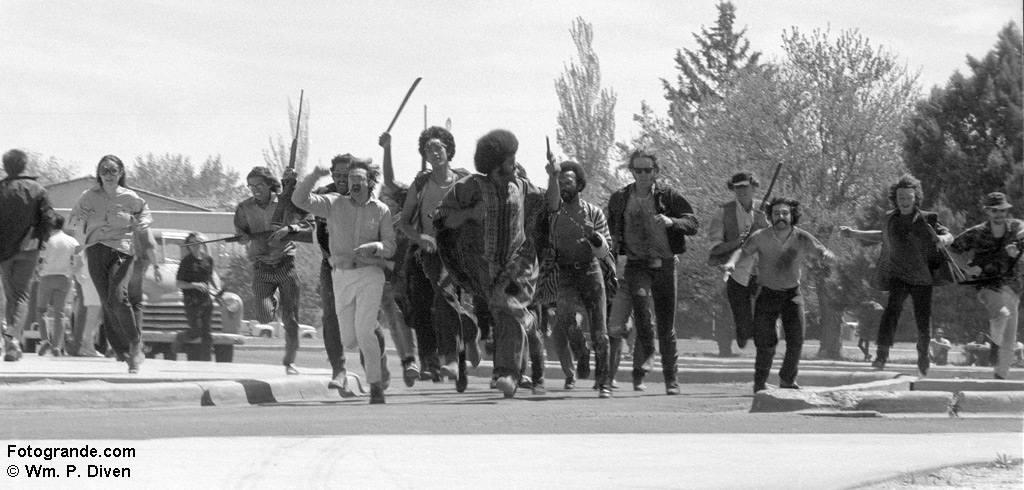

Throughout the war protests might draw 200 counting undercover cops and the photojournalism students who sold pictures to police on the side. The heavy stuff of pepper gas, police sweeps, mass arrests and a fire razing the art barracks came later when the regents summarily executed an experimental program allowing men and women to visit each other’s dorms. Disrupting nature that way united everyone — radicals, jocks, engineers, foreign students, cowpeople, geeks and Greeks — in three-days of rock throwing and vandalism lauded in Aggie history as the Great Sex Riot of 1973. But I digress.

During the war popular sentiment tagged the University of New Mexico, 225 miles to the north in Albuquerque, as the state’s liberal hellhole. There a sexually explicit poem in an English class propelled legislative inquisitors on a decadence hunt through the state’s colleges, and National Guard troops quelled one campus war protest by bayoneting a few demonstrators and journalists. The aw-shucks Aggies only made national news when ag and home-ec students published their list of demands, a tobacco-in-cheek list including hat racks and cuspidors in their classrooms. And then we only made Paul Harvey. Good day.

Don’t get me wrong, I really am proud to be an Aggie and use the term cow college with honest affection. I like the “A” decal facing traffic from the back window of my Jeep because I can read it in the mirror. And tangible benefits accrued from the Aggie image as hayseed conservative with fertilized boots: The inhibiting male-female ratio shifted favorably as parents scared senseless by heathen Albuquerque sent the flower of New Mexico womanhood southward to our humble campus. That, however, is not a tale of politics, and this is.

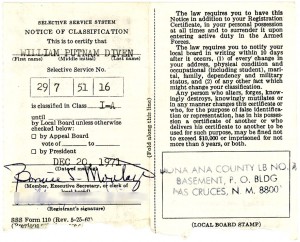

With a gullibility born of paranoia, NMSU banned a chapter of Students for a Democratic Society in hopes the war would take a hint and go elsewhere. The administration permitted a Young Americans for Freedom chapter creating a breeding host for future lawyers, legislators and federal political appointees. We rather ungenerously called YAF the Nazi Youth even though their national organization, for reasons unrelated to our own, refused to endorse Dick Nixon for reelection. If nothing else Aggies staked out political turf and fought for it. Yet in our corner of the desert many rabid anti-war types were either too angry or too stoned to register to vote even though a constitutional amendment in 1971 finally dropped the voting age to 18.

Those 18-to-20-year-old New Mexicans harboring some idealism joined traditional parties, about 15,000 for the Democrats and 9,000 for the Republicans. Two hundred more signed up with La Raza Unida, Peace and Freedom or Socialist Workers, and another 2,000 said the hell with it and professed independence. This shaggy voter couldn’t resist signing up Republican. For that blame a childhood in Abe Lincoln’s Illinois in a family Republican since the Civil War represented in Congress by old-fashion conservatives careful on spending but moderate on social issues. They were Rep. John Anderson, the latter-day independent presidential candidate, patrician Sen. Charles Percy and gravel-voiced Sen. Everett Dirksen. Even “liberal Republican” New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller turned up for a 1963 rally in our one-stoplight county. The darkest side of Democratic politics festered only 98 miles down the Burlington Route railroad tracks where Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley’s machine kept power by brute patronage and brute force unleashing his war dogs outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

In New Mexico, a pilfered section of Old Mexico, politicians campaigned in English and Spanish, and Democrats held most offices most of the time. High-profile Republicans seemed scarce as bland jalapeños since the seriously ambitious passed as conservative Democrats to get ahead. I started out supporting what was then Democrat Lyndon Johnson’s war in Indochina, but at Mayfield High School U. S. history teacher Charles Rivera (aka Carlos Ramón Rivera Martinez el segundo) unwittingly changed that. Or maybe he knew exactly what he was doing as we dissected the Mexican War as local history mixing in muckrakers and robber barons while the Vietnam War daily consumed treasure, national prestige and friends’ older brothers.

The Vote 18 campaign spread among high schools and elsewhere and succeeded with the 26th Amendment ratified by the states in the record time of barely three months. New Mexico law forbade crossover voting in party primaries, but registering as a Republican in that mean era offered a special benefit: two shots at Dick Nixon in June and again in November. Not that Dick Nixon could be voted out despite my Democrat pals sacrificing beards and braids to lose the appearance of drug-hungry trick-or-treaters as they campaigned door-to-door. Besides and as it turned out, booting His Milhousness from the White House would have spoiled the Watergate party.

Part II: The involuntary presidential candidate

While we played at politics in southern New Mexico, the real rumble started quietly up north in Santa Fe. For this cite Katharine Van Stone Mayer, a native New Mexican deceptively nicknamed Peach, whose social conscience formed as a 1930s welfare worker watching Democrats dispense aid based on party loyalty. (Republican corruption was less pervasive due mostly to falling from power when their leader, Sen. Bronson Cutting, died in a 1935 plane crash en route east to fight a Democratic challenge to his reelection.) Stricken with integrity, Peach became a Republican, mastered party intricacies and ran both of Dwight Eisenhower’s presidential campaigns here in the 1950s. Dick Nixon, Eisenhower’s vice president, asked her to do the same for him in 1968, and she accepted pending his written promise to pull all U. S. troops out of Vietnam within six months of the inauguration. He never called again.

Peach fervently opposed the war, as did her son Tom, a writer and occasional Playboy contributor, who first reported from Vietnam in 1966. There his vague anti-war sentiments transformed into the frothing belief Nixon should be tried for war crimes. Back in the United States, Tom briefly endured Washington as press aide to family friend Manuel Luján, New Mexico’s new Republican congressman. From that post he spotted Pete McCloskey’s disenchantment with the war. So when his mother needed a reputable Republican to balance local Democrats on an anti-war panel in Santa Fe, Tom recommended the California congressman, who accepted Peach’s invitation to visit the old Spanish capital.

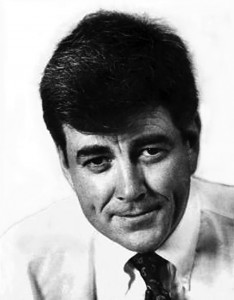

Some months after his trip to Santa Fe, McCloskey stepped into the presidential race as an anti-war candidate. At 44, he appeared the perfect Republican to toss the debate onto Dick Nixon’s doorstep: Korean War veteran with a Navy Cross, Silver Star and two Purple Hearts, lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps Reserve, just a touch of gray in his JFK pompadour. “By every standard of neatness he belongs more in the FBI,” author Norman Mailer wrote in his election reportage. “(He is) the only Republican militantly against the war in Vietnam who has the look of a real conservative.” With no chance of hijacking the nomination, McCloskey entered the New Hampshire primary and a few others.

“My concern really had started on my third visit to Vietnam in late March or early April 1971,” McCloskey told me. “The whole war was so debilitating to everything that I’d been proud of about our country, the Marine Corps, the services. It just seemed the wrong war in the wrong place. I didn’t run for the presidency expecting to be president; I wanted to force a debate on the Vietnam War if I could well before the following November, and if we could force the president to debate the issue in New Hampshire, it was possible a strong vote against Nixon might force him to get out of Vietnam sooner.”

McCloskey’s ideas already had cost him one close friend: John Ehrlichman, his debate partner at Stanford Law School and Dick Nixon’s assistant for domestic affairs. McCloskey reached Congress in 1967, and Seattle lawyer Ehrlichman arrived with Team Nixon in January 1969. “We stayed friends until I made my first speech suggesting the Cambodian invasion was an impeachable offense,” McCloskey said. Reconciliation came on Thanksgiving several years later when McCloskey visited the federal penitentiary in Arizona where Ehrlichman did his time for Watergate crimes.

The McCloskey circle ruled out a vigorous national campaign unless at least 20 percent of New Hampshire primary voters said, “Dump Dick.” Coming up a fraction short, and with his own re-election filing deadline about to pass, McCloskey withdrew to fight the war within Congress. Meanwhile in Santa Fe, Peach and Tom Mayer swooped into the secretary of state’s office, paid the $500 filing fee, and on their own put McCloskey on the June 6 Republican primary ballot. This would be the state’s first presidential preference primary, a replacement for party conventions touted as an attempt to draw publicity to the state. McCloskey campaigned not at all and still attracted 3,367 votes to Dick Nixon’s 49,067. It was enough, though. Under state party rules McCloskey now stood entitled to one first-ballot delegate vote at the national convention.

“I guess those were 3,300 of Peach and Tom Mayer’s friends and whatever peace-and-liberal Republicans there were in New Mexico,” McCloskey concluded. He got at least one vote in every county and finished a few hundred votes ahead of “None of the names shown.” Nationally Democrats clung to South Dakota Sen. George McGovern, the ambulatory survivor who outlasted the Muskie, Jackson, Humphrey, Lindsay, McCarthy, Chisholm and Yorty campaigns. New Mexico Democrats, including most first-time voters, gave him 51,000 votes. McGovern divided his New Mexico delegates with Alabama Gov. George “Segregation Forever” Wallace, who finished a close second in our Western outpost of the Confederacy three weeks after being gunned down at a Maryland mall.

On Wednesday Tom Mayer woke up in wonder. “We didn’t really expect anything to happen because he had officially withdrawn, and there was no way we could get the $500 and the newspaper ads back,” Mayer recalled. “We certainly were not running an active campaign. God knows what would have happened if he’d really been out here and we’d run a campaign. Knowing him as well as I do now, we might not have gotten any votes or might have done much better than he did. He’s a very attractive campaigner, actually; he’s just intractable and not very tactful. So here we wake up the next morning and we’ve got a goddamn delegate. And we say, ‘What are we going to do?’ I guess I must have met (McCloskey) by then because he called up and said, ‘Gee this is wonderful. Tom, I want you to be the delegate.'”

It would not be that simple. McCloskey remembers most New Mexico Republicans as nuke-Hanoi types, and Tom suffered from his self-described image as a “half-assed college professor who writes for Playboy and is liable to get up there and give The President the finger from the podium.” Nixon forces chapped by the primary debacle armed themselves for battle at the July state convention in Albuquerque. Behind the scenes where she worked best, Peach Mayer found an ally in Anderson Carter, a 1950s Democrat turned ’60s Republican who managed Barry Goldwater’s New Mexico campaign in 1964. A hard-rock conservative, he had little taste for McCloskey. “Peach called me about Tom being McCloskey’s delegate,” Carter said. “I owed so many favors to that woman, there was no way I could say no. I went up there and tried to get it done.” And son of a gun, he almost did cashing IOUs around the state.

Former Gov. David “Lonesome Dave” Cargo, just beaten in the Republican U. S. Senate primary by former Albuquerque City Commissioner Pete Domenici, chipped in, too. Despite a mutual hostility, Carter and Cargo labored for McCloskey and his would-be delegate.

Eleven days after the New Mexico primary, Washington police busted five burglars in business suits at Democratic National Headquarters in the Watergate complex. Presumably in that interim The President and his convention gurus found time to squirm over two chilling implications of McCloskey’s remote victory. First was the loss of unanimous first-ballot renomination, embarrassing but nontoxic given the GOP in the 20th century only bestowed that love offering on Ike, William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt. But second came the loathsome spectacle of Tom Mayer, errant author and academic, turning his McCloskey nominating speech into a nationally televised 30-minute trashing of Dick Nixon and the war. This fear transcended routine Nixonian paranoia, perhaps from eavesdropping on the phone conversation when McCloskey asked Mayer how he would handle his opportunity to rip The President. Mayer told McCloskey, “My inclination is to tell it like it is in words of one syllable. I think he should have been up there right in the dock at Nuremberg with Hermann Göring.”

So Nixon operatives dropped their hammer on New Mexico. “They wanted to try and cheat, really, that was what it was all about,” Cargo said as we sat in his Albuquerque law office. “They were saying, ‘Well, just select someone to get down there (Miami Beach) and get up and say, the hell with it, this is a lost cause, and vote for Nixon.'”

As the state convention neared, McCloskey had the votes to make Mayer his delegate. Yet when the smoke cleared in Albuquerque, Nixon forces had lost the battle but won the war fought in a broiling high school gym with dead air conditioning. All went well for McCloskey until someone asked whether he planned to support The President after the national convention. McCloskey said sure, if he stops bombing North Vietnam. That rankled party loyalists, and Carter’s carefully gathered chits began to scatter. McCloskey kept his delegate vote but narrowly lost the rule change needed to have his own flesh-and-blood delegate. The onus of casting the McCloskey vote fell on Congressman Luján, who would lead the delegation and deliver one of the Nixon seconding speeches. McCloskey and Mayer then began planning their convention appearance as national anti-war theater.

Part III: Guerilla theatrics and the veterans’ march

With a month remaining before the national convention, the White House still had time to corral New Mexico’s rogue vote. Luján, later the first President Bush’s secretary of the interior, told me no one ever suggested he ignore state law at the convention. Instead that dubious honor found its way to Cargo, the maverick político dubbed Lonesome Dave by an old Hispanic sheepherder ambushed on the range by Cargo during his low-budget, no-entourage campaign for governor. Roundabout hints stole in from the White House staff and the Republican National Committee.

“The thing was that they ran a very strange operation because you never really knew if Nixon was aware of what they were saying or not,” Cargo said. “It was always difficult to tell how it came out of the White House because you never really heard. A lot of times Nixon would get involved; I mean if he wanted something done, he would say so. He used to call the governors quite frequently like when he was naming his cabinet, God he’d call us. Nixon was very good about that.

“Nixon, he was an interesting guy, and I think not at all as the public perceives him, or even the press. He’s a very shy, kind-of withdrawn person. But at the same time he was a consummate politician. It wouldn’t have been totally out of character for him to have called, say, ‘Hey now, you know, c’mon, let’s get rid of that damn delegate.’ But he didn’t do that. But there were people in the White House who made it pretty clear they didn’t want any delegate there who would cause any ruckus, and they would subtly go at it.”

Handling Cargo required delicacy. At the 1968 Republican convention, also held in Miami Beach, he fumed on national television about similar illicit pressures when he was the lone Rockefeller pledge in a state delegation split between Dick Nixon and Ronald Reagan. Any overt attempt to subvert the 1972 process might spread the problem party wizards were trying to contain. (I watched that 1968 speech at a summer camp in Wisconsin. My co-workers asked what was wrong with my governor, and I didn’t have an answer, then.)

Meanwhile McCloskey and Mayer faltered in attempts to penetrate the convention. Act One called for Mayer piloting his indecently yellow biplane, a Beechcraft Staggerwing, to deliver McCloskey to Miami International and a waiting CBS News crew. “He made a request for parking right next to Air Force One, and of course the (convention) staff went ballistic,” Luján said. Needless panic, as it turned out. Mayer nursed the ancient aircraft into the South, but McCloskey wasn’t there. Probably called back to Washington, McCloskey said; more likely on a Sierra Club hike, according to Mayer. “Highly telegenic, it would have made a marvelous contrast to Air Force One,” Mayer said. “It really would have been a superb piece of theater.”

That still left Act Two, the indictment as nominating speech. Or did until Nixon soldiers engineered a rule — purportedly to avoid endless favorite-son speeches for home-state candidates — requiring a candidate hold majorities in three delegations plus a minimum delegate count to earn a nominating speech. The credentials committee also upheld the state decision denying McCloskey a live delegate. Instead the only microphone available for anti-war commentary went to Michigan Rep. Donald Riegle during a token appearance before a platform subcommittee. There Riegle, who helped launch McCloskey’s campaign the year before, complained about the party squelching debate on a critical national issue simply to avoid embarrassing The President. “We got shafted at every turn,” Mayer said. “The word was clearly in: screw these people. They never even listened to us politely.”

Act Three relied totally on improvisation beginning when a thousand or so Vietnam Veterans Against the War marched, hobbled and rolled to Republican headquarters at the Fontainebleau Hotel. No pampered longhairs, the simple presence of these battle-hardened veterans intimidated several hundred increasingly tense riot police. “Pete said, ‘We’ve got to see if we can help,'” Mayer recalled. “We’re trying to get through the lines to talk to these people, and a cop turns around and tries to whack McCloskey in the gut with a billy club. Pete very calmly deflected the club, pulls out his congressional ID and gives this guy a chewing out. McCloskey wasn’t a Marine for nothing.” McCloskey and Mayer brokered negotiations between VVAW leaders who wanted into the hotel and convention officials who wanted no part of it.

“I went out, and Tom, bless him, went back (into the hotel) and got a case of Coca-Cola,” McCloskey remembered. “It was just hotter than hell out there with that sun coming off, baking the asphalt. Tom came through with a case of Coca-Cola to cool these guys off, give them a cold something to drink. They passed the Cokes out, and that really scared the officers because now these guys had weapons. I could see a couple policemen kind of shaking in their shoes. They were big, tough and they had all the weapons alongside that line. They were going to stop these kids, but the kids were combat veterans. I got the impression the police would be just as happy if they didn’t have to take them on.

“In any event the thing was compromised, and as I recall it was agreed three of the guys would be allowed into the hotel, and at least one of them was in a wheelchair. So Tom and I went back into the hotel with the three leaders of the group and averted what otherwise might have been a fairly interesting riot. It would have been a terrible thing for those officers to have started clubbing combat veterans, and they might not have won.”

Even as late as nomination day, Aug. 23, it appeared Dick Nixon’s fixers expected New Mexico to see the light. At least that’s what they indicated in the precise, minute-by-minute script they prepared for general convention chairman Gerald Ford, the Michigan congressman soon to replace tax cheat Agnew as vice president and then assume the presidency as Watergate flushed the White House clean. Republican couriers mistakenly delivered script copies to several convention pressrooms where reporters noticed the roll call of the states ended with The President receiving every delegate vote. But that night, when Ford called on New Mexico, Luján stepped to the microphone and cast 13 votes for That Great American Richard Nixon, apologized for the requirements of state law, and reported one vote for McCloskey. Team Nixon still got the last dig when the big-screen projection of the final tally showed 1,347 delegates for Nixon and one vote for “others.”

McCloskey and Mayer managed a final bit of theatrics the next night as they used gallery passes to infiltrate VVAW members into the convention for Nixon and Agnew’s acceptance speeches. During the tumult the vets waited as TV cameras scanned the crowd before focusing on them. Then they pulled out crude cardboard signs from under their wheelchairs. “The minute that went out, of course the television played it,” McCloskey said. “Here’s the three kids in fatigues and Silver Stars and Purple Hearts holding up the three box tops saying ‘Stop The Bombing.’ All of a sudden you see this wave of red-white-and-blue Nixonettes, just little pompon girls in red-white-and-blue miniskirts, they just descend and just engulf these three guys in wheelchairs and push them out the door out of the gallery. That was the one happy scene of the whole convention.”

One of the vets was Ron Kovic whose memoir of war and anti-war, “Born on the Fourth of July,” credits the Secret Service with wheeling them from the arena and quickly chaining a door before the press could follow. The next morning after a late dinner, McCloskey returned to his hotel suite and nearly tripped over a sleeping staffer who said both bedrooms were occupied, one by Daniel Ellsberg and his wife, the other by Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda. McCloskey knocked on the door of an aide’s room and slept there on the floor.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Epilogue ~ 1992

Two decades later Dick Nixon walks around dragging another toe tag from the political morgue. Older and jowlier, no longer terrorizing the partisan jungle like King Kong in blue serge, he still holds audiences for 30 minutes of complete subject-predicate sentences with neither notes nor TelePrompTer. Most of his hirelings served their jail time or retreated into relative anonymity save those running for president this year. I wrote to him asking about 1972, but haven’t heard back yet. Pete McCloskey practices law in the Bay Area, and Tom Mayer continues to teach, write and fly the Staggerwing. Peach Mayer died in 1985, five years after the 75th birthday party where her well-wishers included John Ehrlichman, her new friend then out of prison and living in Santa Fe, and his old pal Pete McCloskey.

And what of our country? After Dick Nixon fled Washington, the party’s hobnailed wing finally dragged the liberal faction into an alley and stomped it stuporous. Vietnam, united now for better and worse, still gets treated like the bully enemy. And under-21 voters still shuffle to the polls but at a rate well below half what it was in 1972. You’ll have to forgive me, this may be the excesses of those days finally catching up to me, but I miss Dick Nixon. You knew where he stood, and it felt good to vote against him. Damn good. But this year it’s a tough call in deciding whom to vote against let alone for. When the primary rolls around I may write in Richard M. Nixon since it’s too late to put his name on the ballot without telling him.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Epilogue II ~ 2014

Forty years ago today — Aug. 8,1974 — I’d quit my first news job and was tooling around the West trashing two credit cards before going back to college. Outside the visitors center at Crater Lake National Park in Oregon a group of us gathered around a Volkswagen Beetle with its radio cranked up and listened to Dick Nixon utter the infamous words, “Therefore, I shall resign the presidency effective at noon tomorrow.” A week or so later we were both in San Clemente, Calif., he hiding out at a friend’s mansion, me at a home not far away volunteer bartending at a friend’s grandparents’ 50th wedding anniversary party. I think I had the better gig.

Pete McCloskey first set foot in New Mexico at the invitation of Peach Mayer, came back for the 1972 state party convention and found himself returning more and more. He would soon bring along Helen, now his wife of 33 years, and she, too, was smitten. They live in northern California but also spend time at a home in rural Santa Fe County.

“I fell in love with New Mexico, I can tell you that,” McCloskey told me recently. The novels of cowboy turned author Eugene Manlove Rhodes deepened the relationship as have his and Helen’s travels taking them to nearly every corner of the state, first with Peach and her son Tom and later on their own. Pete and Manuel Luján, who served in Congress together, remain friends.

Nixon and most of his crew are gone now, but not John Dean, the White House counsel heard on a March 21, 1973, Oval Office tape warning Nixon the cover-up of the Watergate break-in was a “cancer on the presidency…that must be excised or the presidency would be in danger.” Dean has written a book called “In Defense of Nixon” newly released as are others timed to the resignation anniversary.

David Cargo, one of New Mexico’s more colorful and quotable governors, died last year at 84. Anderson Carter also is gone. Tom Mayer, I’m told, divides his time between New Mexico and Old Mexico and may or may not still have the Staggerwing. I left a message at what I think is his phone number but haven’t heard back.

Like 1972, this election year of 2014 is ripe for choosing sides even though we’re not picking a president. Too bad, though, if you missed our June 3 New Mexico primary because you didn’t register, pick a political party or just tuned out. Registrations of about a million voters here split 47-31 Democrat versus Republican with the other 22 percent declining to state a party preference or at least choosing one of five recognized “minor” parties.

Under state law primaries are party affairs intended only to pick a candidate for the general election although a lawsuit is trying to open them to everyone regardless of affiliation. Truth is a lot of races are decided in primaries when the other party can’t get it together to field a candidate. Yeah, an open primary might get more voters out in June, but does that do anything to make folks think about where they stand and commit to either of the major parties, both of which need reforming from within? We’re just about out of our latest wars, but reviving the military draft or some kind of compulsory national service would certainly motivate young people to track who is representing them and why.

By the time I got my draft card in high school I was part of the now almost forgotten Vote 18 movement arguing if you were old enough to fight and die for your country, you were old enough to vote for the people putting you in that position. We won the argument although I’d turned 21 by my first election in 1972. That year Nixon exalted in the peak of his national and world power after losing the 1960 presidential race to John Kennedy and the 1962 contest for governor of California to Edmund Gerald “Pat” Brown, father of current Gov. Edmund Gerald “Jerry” Brown Jr. After that last defeat, Nixon famously retired from politics telling the press, “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore.” It wouldn’t be the last time he misled us. The closest Nixon came to a public apology after his resignation happened during his 1977 interviews with British journalist David Frost when he conceded he’d let the country down.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Adult content

Two anti-Nixon slogans from the late 1960s and early ’70s:

- Dick Nixon before he dicks you.

- Why change Dicks in the middle of a screw; vote for Nixon in ’72.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Correction:

An earlier version of this account erroneously identified prominent New Mexico Republican Anderson Carter by his son’s name, Anderson Carter II.