Shaggy clouds brush South Dakota’s jagged Badlands as our pickup crosses tracks left on a Christmas Eve long ago by people seeking safety but trudging toward massacre.

Bighorn sheep ignore the spits of rain annoying tourists already grumbling about the vigorous wind and the lack of postcard light on the raw colors of Badlands National Park. At a pulloff a plaque in seven sentences plots the Big Foot Trail describing the flight of Minneconjou Sioux.

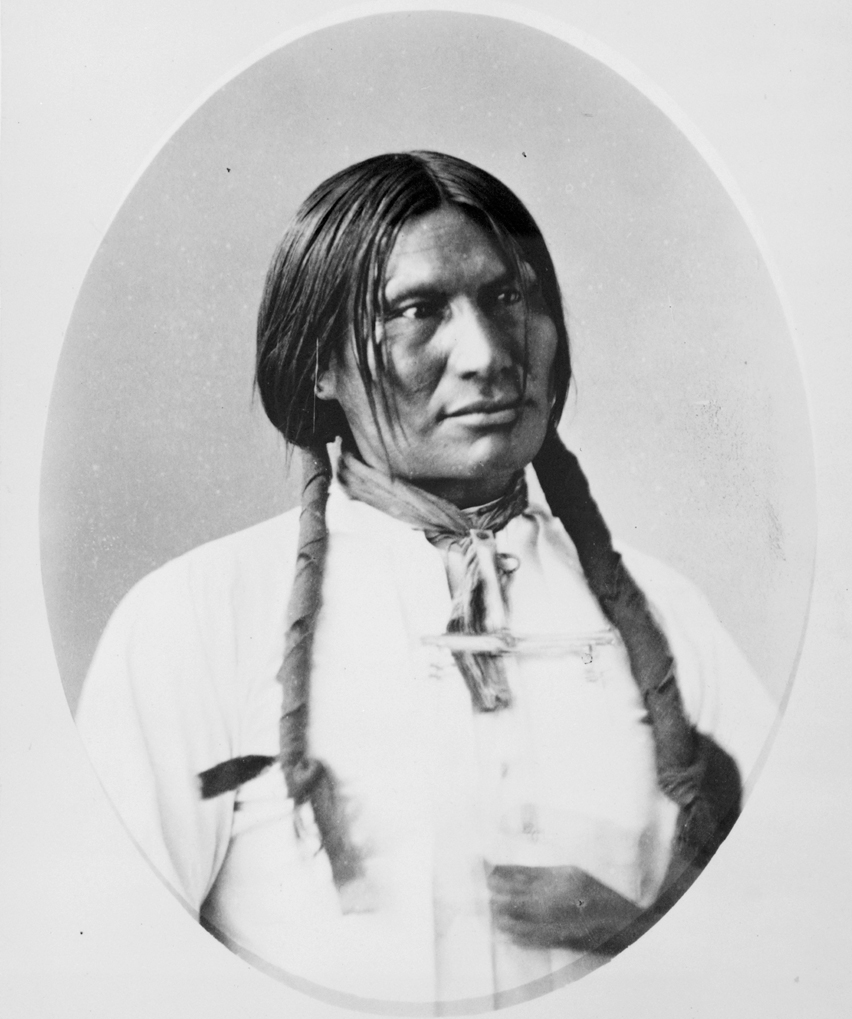

Here the chief, known to his people as Spotted Elk and whites as Big Foot, rested ill with pneumonia during the hours spent molding a sharp descent off the Badlands Wall into something passable for hundreds of men, women and children. This was two weeks after federal Indian police sent to arrest Sitting Bull instead killed him and perhaps a dozen others on the Standing Rock Reservation.

Word of the killing sent Spotted Elk south toward the snow-covered valley along Wounded Knee Creek on the Lakota Sioux reservation at Pine Ridge.

The trail he followed, and the path we soon chose, led down a dark alley of Manifest Destiny.

Near the center of the Great Plains spreading from Texas to Alberta, where railroad tracks and cross-country highways follow the Oregon Trail, evidence of America’s westward push is everywhere, if you choose to look and to see. Less visible and clinging to their cultures are the survivors who, like the buffalo, nearly vanished in the name of others’ self-proclaimed future.

One war might be a mistake. A long series of wars is a pattern. Indians were the original terrorists in the American imagination. — Author Viet Thanh Ngueyen, American Like Me: What it means to love my county, no matter how it feels about me, Time, Nov. 26-Dec. 3, 2018

The path of Spotted Elk and about 350 followers from the Badlands to Wounded Knee Creek, known today as the Big Foot Trail, leads through serene hills rolling in shades of ochre and dotted with homes and occasional communities. On this Sunday morning in late September, clouds already weeping appear ready to fall from the sky.

A few vendors braving bitter gusts set up beside Bureau of Indian Affairs Route 27 hawking their crafts from open stalls between a parking lot and the killing field. For $20, Jessica, underdressed for the stinging chill, sells a dream catcher assembled with cedar twigs and horsehair.

She gathered materials from the people’s land where ghosts walk, and her sacred hoops work overtime to give good dreams a chance against tough odds.

On a hilltop across the highway, a monument marks the mass grave dug in 1890. Beyond that once stood Sacred Heart Catholic Church prominent in news photos of the 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee by the American Indian Movement (AIM) in 1973.

Fire razed the bullet-ripped church soon thereafter. Its replacement, abandoned by the church, opens now as an ad-hoc youth center where a few volunteers strive to shield young people from alcoholism, violence, inadequate schools and other traps littering the path to their futures.

The First Battle at Wounded Knee

On Dec. 29, 1890, snow covered this ground when soldiers were ordered to disarm the wary Minneconjou. After a first shot the bodies piled up fast with estimates of Indian dead reaching 300 with Spotted Elk among them.

The shooting also killed 20 soldiers from the 7th Cavalry. This would be the unit famously commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer before his death overlooking the Little Bighorn River in Montana.

The Army awarded 20 Medals of Honor for what it called a battle and the Sioux called a massacre.

HEAP GOOD INDIANS. The Terrible Slaughter at Wounded Knee. FOUGHT LIKE FIENDS – OMAHA, Dec. 30. – It was a war of extermination now with the troops; it was difficult to restrain them. Tactics were almost abandoned. About the only tactics were to kill while it could be done. — Unnamed Special Correspondent for The Bee, Omaha, Neb., Dec. 30, 1890, republished in and headlines by the Los Angeles Herald, Dec. 31, 1890.

From Wounded Knee a direct line flies 300 miles northwest to the battlefield at Little Bighorn passing over Custer, S.D., the Black Hills city named for the Civil War hero and martyr to Manifest Destiny. Like Pearl Harbor and 9/11 in the centuries ahead, the annihilation of Custer and about 270 men of the 7th roiled the country amid cries for vengeance.

The direct line back to Wounded Knee is only 14 years. That’s the passage from 1876, when the Sioux, Western Cheyenne, Arapaho and their allies destroyed Custer “in the time it takes a man to eat a meal,” to 1890 and the 7th opening fire at Wounded Knee.

For we two travelers this timeline compresses below two weeks after a wintry slap at northwest Wyoming disrupted a long-planned road trip to Yellowstone. By then we’ve unhitched our one-axle travel trailer in the northeast corner of the state beneath Devil’s Tower, the fluted spire sacred to multiple tribes and a draw for rock climbers.

It’s also sacred to fans of the 1977 movie “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” How else to explain those fearful of alien probes posing in tinfoil helmets with the nearly 900-foot pillar in the background?

Layering maps on the table the size of our Scrabble board reveals Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument 200 miles northwest in Montana. It’s only raining there, and a roundtrip and a push east drops us in South Dakota, the Badlands and the Black Hills, where it’s chilly damp but too warm for snow.

At the Wyoming Highway 24 stop sign previous planning ends. A left takes us north and west across the Western Cheyenne nation and into the lands of the Crow people whose agency surrounds the battle site. This is new territory for us, long read about but never felt in person. Within hours the detour evolves into a 10-day connect-the-dots exercise in clashing cultures and human suffering.

On The Wisdom of the Crow

The Crow sooner than most stared forward with clear eyes seeing a trail forking toward a bleak future. The vision of going left or right yielded the same truth: buffalo vanishing as white soldiers, settlers and fortune seekers multiply.

So instead of resistance they chose accommodation with the invaders albeit with little hint of submission led by the Crow chief Alaxchíia Ahú, remembered by one culture as Plenty Coups.

“We made up our minds to be friendly with them, in spite of all the changes they were bringing,” Plenty Coups told a biographer in the 1920s. “But we found this difficult, because the white men too often promised to do one thing and then, when they acted at all, did another.”

He advised his people, “Get a white man’s education. Without a white man’s education, you are his victim. With an education you are his equal.” He was less sanguine, however, about white man’s religion with its too many forms and too many disagreements over which was the right one.

This bothered us a good deal until we saw that the white man did not take his religion any more seriously that he did his laws, and that he kept both of them just behind him, like Helpers, to use when they might do him good in his dealings with strangers. … We have never been able to understand the white man, who fools nobody but himself. — Chief Plenty Coups (1848-1932) quoted in Frank B. Linderman, Plenty-coups, Chief of the Crows, John Day Co., New York, 1930. (New Edition, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2002)

Crow warriors, never bashful about warring with the Sioux, rode with Custer as scouts and tried to save him from himself foretelling the uneven fight at Little Bighorn. When offered the option to leave, they did.

The Somber Site of Custer’s Hubris

In my youth nearly every school boy and many girls knew Custer’s Last Stand, or at least the textbook or Hollywood versions: Gallant soldiers, whooping savages and tragedy befalling the Civil War’s boy general. Actor Victor Mature as Crazy Horse, anyone?

A disturbing tale told by a teacher shortly before we left New Mexico amplified our curiosity. The battlefield enthralled him, he said, but not one of the high school boys he led on a Western tour knew of Custer or his fate.

Over time Custer’s star faded as the glorious warrior morphed into imperialist stooge often leaving detail and nuance in the dust.

Reservation schools fare poorly at history as well. While reporting a story on The Long Walk, the 1860s peak of brutality in subjugating the Navajo people – the Diné — I interviewed Dr. Jennifer Rose Denetdale of the University of New Mexico history faculty.

Denetal, the product of a “raggedy rez education” and a culture averse to speaking of the dead, only learned in adulthood of her own family’s close connection to the Long Walk.

“Americans are not willing still and are woefully ignorant of the treatment of indigenous people including the Navajo people in this country. … It’s still the case that a lot of young Navajo don’t know this history because of ethnic cleansing, because of American education, which is ethnic cleansing. And that we’re still recovering ourselves and that knowing these stories are also part of, a very important part of our historical experiences and a part of who we are as Navajo people. Whether or not you want to talk about them, whether or not you say it’s not traditional to talk about them, we’re still talking about them and we still remember.” — Dr. Jennifer Rose Denetdale, interview, April 19, 2018.

In June 2018 the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, the Navajo Nation, a descendant of a peace commissioner and others joined in remembering the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Bosque Redondo. The document – ratified by the Senate thereby treating an Indian tribe as a sovereign entity — freed the Diné from their concentration camp to walk back to the Four Corners and their homeland, today the largest reservation in the country.

The Legacy Lingers

Beyond his own quirks and ego, Custer served as a blunt instrument of White House, Congressional and War Department policy flavored by mining, ranching and religious interests. With two years still to live, he commanded the Black Hills expedition striding into the corner of South Dakota already designated the Sioux reservation. There he confirmed the presence of gold in the Black Hills knowing his report would touch off a stampede and likely a war.

Just outside the Black Hills, Rapid City, S.D., tries with mixed results to reconcile the past and present. It celebrates the 7th Cavalry in its veterans’ parade although Native Americans – who serve at a higher rate than other services members — rarely participate. Even McDonalds bumps against cultural lines.

“I buy a Happy Meal for my daughter only to find a 7th Cavalry Custer doll inside. She gets upset when I try to explain why I think it belongs in the trash. … In a jewelry shop along Mount Rushmore Road, I look at the gold for which my grandparents’ territory was invaded and spot a wine-bottle holder depicting a Native chief chugging a bottle of wine.” Evelyn Red Lodge, Rosebud Sioux, in High Country News, Sept. 21, 2017.

Rapid City is far from alone in showcasing the popularized version of the Wild West. The Black Hills are a recreation center where stores in downtown Custer tout Black Hills gold among the souvenirs for sale. Rare is the tourist among the flocking hordes who upon first seeing the presidential busts chiseled on the face of Mount Rushmore thinks first of Custer or Manifest Destiny.

Trace the conflict of cultures to religious refugees dropping anchor on the Atlantic coast early in the 1600s. Immigrants soon began gnawing westward feeding on land that, from one Christian perspective, awaited free for the taking because the natives weren’t putting it to productive uses.

The Puritan side of my family missed the boat to Plymouth Rock but arrived in time to experience the Salem Witch Trials. For them the devil very much lived and breathed.

‘The association among Indians, black men, and the devil would have been unremarkable to anyone in the Salem Village meetinghouse. English settlers wherever on the continent had long regarded North America’s indigenous residents as devil worshippers and had viewed the shamans as witches. Puritan New Englanders, believing themselves a people chosen by God to bring his word to a previously heathen land, were particularly inclined to see themselves as antagonists of the ‘devilish” Indians.” – Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2002, p. 59

A century almost to the day after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, indigenous warriors smashed Custer and the 7th Cavalry. Yet if anything the victors only hastened the new world foreseen by the Crow people.

From the tawny bluffs above the Little Bighorn River, a camping ground and battlefield return to life. In the verdant valley stretch mobile cities of teepees erected by the women where clans gather under treaty rights to hunt off the reservation. Part of the cavalry rushes in from upstream quickly realizing their error. Soldiers retreat across the river into the hills and draws pursued by Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and a warrior army as Custer arrives on the scene marked today by monuments and a national cemetery.

Peace now vibrates with horn blasts proclaiming the ceaseless parade of coal trains from the Powder River country passing in review. Explanatory markers, ranger talks and the addition of a Native American memorial on the flank of Last Stand Hill show how Custer’s star waned to the point Congress in 1991 erased “Custer” from the renamed national monument.

The shredding of indigenous society and hundreds of thousands if not millions of people began with growing bites of persuasion, fraud, superior arms and force of numbers. While Manifest Destiny gets little play in dominant society, it remains connected to the people in its path.

“The political, social, and economic tensions on the reservation have roots that can be traced back to the landing at Plymouth Rock. The result on most, if not all of South Dakota’s six Indian reservations, is a situation so vastly complex that a solution may never be possible.” Unnamed Pine Ridge resident to UPI reporter Patrick J. Little, June 1975

The comment above came after two outnumbered FBI special agents died in a nighttime shootout at White Clay Creek not far from Wounded Knee and as at least 200 federal officers with air and armored support swarmed the rez. If you’ve not heard of Leonard Peletier, he’s the AIM member imprisoned for the agents’ deaths and the subject of an ongoing campaign challenging the case against him.

(Peletier, serving two life sentences, became eligible for parole in 1993. Shortly before leaving office in January 2025, President Joe Biden commuted his sentence to permanent home confinement without pardoning Peletier for any underlying crimes. After 49 years of confinement, Peletier, at age 80 and in ill health, settled into a home in Belcourt, North Dakota, on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation.)

Manifest Destiny does still invade the public discourse as it did in December 2017 to take a swipe at New Mexico’s acting cabinet secretary for public education. In a speech to a charter-schools group, Christopher Ruszkowski listed Manifest Destiny among the nation’s “fundamental principles” akin to freedom, choice and competition.

Tribal leaders promptly called his remarks disgraceful, insensitive and lacking in understanding of the damage wrought by white society. About 10 percent of New Mexico’s two million people are Native American.

Ruszkowski expressed remorse for poor word choice and ignored calls to resign. Yet he allowed a spokesperson to refer to one critic – a Navajo woman, elected state regulator and former state senator – as “pathetic.” Ruszkowski departed as a Democratic administration assumed office in Santa Fe on Jan. 1, 2018, after eight years of Republicans in charge.

Even the current president on the United States, known neither for restraint nor appreciating history, gleefully employed the Wounded Knee massacre to mock a political rival this month. “This isn’t funny, it’s cold, callous, and just plain racist,” a Sioux writer responded on Twitter.

On the Trail of Fears

Over the course of our road trip some familiar dots connected: Custer, the Fetterman massacre, Crazy Horse and Pine Ridge. Others collated slowly: Grattan, Wyo., conjuring an 1854 treaty violation leading to the deaths of 2nd Lt. John Grattan and all his small command; Crow Chief Plenty Coups, White Clay Creek, and Kate Bighead, witness to Custer slaughtering Cheyenne at Washita, Okla., in 1868 and his downfall at Little Bighorn.

All around flowed traces of boots and saddles, moccasins and painted ponies, bugles and medicine bundles. We trod an ancient continuum neither history nor current events. What was and what is merge. Fenced bison extrapolate into thundering millions. Coal becomes gold. The line between tourism and trespass blurs as time, space and struggle unite.

Some saw the Wounded Knee Massacre as the end of the Indian Wars. Instead there followed the mostly cold war of active neglect, land theft, discrimination, education as cultural suppression, forgotten treaties and government mismanagement and mistreatment.

Here in Sandoval County, N.M., home to all or part of 10 pueblos and the Navajo and Jicarilla Apache nations, the U.S. Department of Justice in 2012 ended years of monitoring elections after the county began genuine outreach to Native American voters. Indigenous people hold state and local offices here, and my congressional district just elected Rep. Deb Haaland as one of the first two Native American women to serve in Congress.

Elsewhere voter suppression runs wild in multiple venues but notably North Dakota with persistent Republican efforts to pass the strictest voter ID law in the country.

“The voter measure was first introduced after Democratic Sen. Heidi Heitkamp’s 2012 victory in a tight race determined by roughly 3,000 votes. Many ballots for Heitkamp were cast by Native Americans.

“The North Dakota Legislature was debating the issue again in early 2017 when President Trump was preparing to sign an executive order to resume construction of the Dakota Access pipeline, the controversial oil project that tribal members and others had protested.

“According to committee minutes, legislators raised questions at the time about suspected voter fraud in the 2016 general election by those living “on the other side of the bridge” — a reference to the months-long road blockade enforced by a militarized police force guarding the pipeline construction.” — Jenni Monet, “In North Dakota, Native Americans face a voter ID law they believe is aimed at them,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 4, 2018.

Monet, an independent journalist and member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, was arrested and jailed on misdemeanor charges of trespassing and engaging in a riot in February 2017 while on assignment reporting on the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests. Prosecutors dropped the riot charge a few weeks before a state judge in a one-day bench trial found her not guilty of trespass in June 2018.

Tribal opposition to the DAPL based on water protection and discounting of treaty rights brought thousands of protestors encamped along the pipeline route near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. The pipeline has been built across the state and under the Missouri River and Lake Oahe just upstream from Standing Rock.

A federal judge twice blocked the ID law finding it would disenfranchise thousands people living on reservations and lacking street addresses and a narrow list of identity documents. Urban and more affluent voters don’t face similar burdens, he wrote.

“The undisputed evidence before the Court reveals that Native Americans face substantial and disproportionate burdens in obtaining each form of ID deemed acceptable under the new law. … The undisputed evidence before the Court reveals that overcoming these obstacles can be difficult, particularly for an impoverished Native American. … The undisputed evidence before the Court reveals that voter fraud in North Dakota has been virtually non-existent.” — U.S. District Judge Daniel L. Hovland, “Brakebill et. al. v. Jaeger, Order Granting Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction,” Aug. 1, 2016, Case No. 1:16-cv-0008

Higher courts overturned the judge in essence finding it more important to protect the state from voter fraud than to enfranchise all eligible voters.

Unlike the poor and ethnic targets of voter suppression, navigating the electoral process can be relatively easy for white follk. On Election Day 2018, it barely took 10 minutes to state my name and the last four digits of my Social Security number, blacken ovals on a paper ballot, feed it into a counting machine and walk out with an “I Voted Today” sticker. Despite some huffing and puffing in a couple of tight races, no complaints of election fraud bubbled up here.

New Mexico, however, is a different place where tribes and pueblos lost the wars but won the peace. That is not to play down lingering problems of respect, education, addiction, discrimination, infrastructure and environmental concerns but to note the survival of the people largely in homelands and with their cultures. The Spanish conquerors — abuses and atrocities notwithstanding — saw the indigenous peoples more as souls for conversion, not extermination.

The tribes practice politics as well asserting themselves most recently as governments worthy of respect and water protectors for not just themselves but the greater community. What began in 2015 as an attempt to drill a single exploratory oil well in new territory here in Sandoval County quickly exploded into a defense of the Albuquerque Basin aquifer and a demand for government-to-government consultations between the county and the indigenous communities.

Tribal governors representing sovereign nations found themselves at County Commission meetings being cut off after three minutes of speaking as were a diverse native parade of activists, energized young people, attorneys, and various other professionals and elected officials. Outside bullhorn-driven protests by coalitions of activists became a regular feature along with threats of the conflict turning into the the next Standing Rock.

The years-long attempt to write and pass a zoning ordinance regulating oil and gas development collapsed under its own weight in December. By then an awakening giant stood in Indian Country among new alliances and unwilling to be ignored any longer.

(Update Nov. 29, 2019: A move is underway in the U.S. Congress to rescind the 20 Medals of Honor awarded 7th Cavalry troopers for their actions in the Wounded Knee Massacre. In that era the medals were handed out for lesser actions than risking one’s life in an act of conspicuous gallantry. The standards for earning a Medal of Honor tightened in the early 20th century. For more on the current congressional action, see: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/11/27/soldiers-got-medals-honor-massacring-native-americans-this-bill-would-take-them-away/ )

(Update Jan. 1, 2025: Congress abandoned attempts to rescind 20 Medals of Honor due to awarding of the medals being a function of the president and Executive Branch and therefore not under the control of the Legislative Branch. In late 2024 a review by the Department of Defense, part of the Executive Branch, ended with the medal awards still intact.)

Thank you