If Albuquerque took a chill pill, it might act more like El Paso, Texas, a metro area of similar size but only half the violent crime.

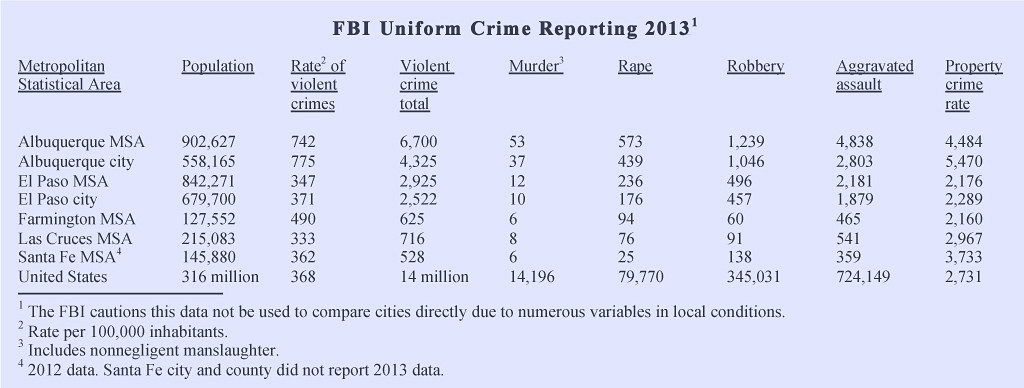

Metro Albuquerque counts four times as many murders as El Paso, a city 250 miles down the Rio Grande opposite Cíudad Juarez, Mexico, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) for 2013. Albuquerque tallies twice as many rapes and in 2013 recorded 742 violent crimes per 100,000 residents, twice the national rate.

El Paso police cordon a downtown street to investigate a pedestrian fatality. Unlike Albuquerque, jaywalking laws are enforced here. Photo © William P. Diven

In comparison to the Wild West shootout occurring almost nightly in Albuquerque, El Paso might as well be Mayberry RFD.

The FBI report covers the Albuquerque statistical area – which includes 903,000 people spread across Bernalillo, Sandoval, Torrance and Valencia counties. El Paso includes one neighboring county and counts 842,000 residents.

El Paso’s low crime numbers changed little in recent years despite fears carnage from the war between rival drug cartels in Juarez would spill across the river. The city responded by touting itself to tourists and business locators as one of the safest cities in the United States.

“I’ve lived in Houston and New York, and El Paso is the safest city I’ve ever lived in,” banker and El Paso native Art Moreno said as he walked through downtown at midday. “It’s always been safe.”

Meanwhile Albuquerque whistled past its statistics while a wave of fatal police shootings brought federal oversight of its police department and aroused black-eye coverage in national and international media.

Yet there’s a problem with the numbers. Even the FBI cautions against using UCR statistics contributed by local departments to rank one city against another.

It’s not comparing apples to oranges but apples to dogs, according to Dr. G. Larry Mays, a Tennessee cop who became a college professor and led the Criminal Justice Department at New Mexico State University until retiring in 2011.

“The UCR is like an iceberg: 10 percent above the water and 90 percent below,” Mays said. “We call it the ‘dark figure of crime,’ the crime that’s not reported to police.”

While the murder numbers tend to be accurate, rape is substantially underreported, as are property crimes, he added.

“I used to tell my students the better work the police do, the worse the crime numbers look,” Mays said.

Still, residents and people familiar with both cities describe distinctly different vibes in culture and law enforcement. El Pasoans, however, quickly dismiss the claim advanced by the 1972 novel “The Stepford Wives” that naturally occurring lithium in their water tranquilizes everyone.

Instead they first cite the massive post-9/11 secure-the-border presence of federal drug, security, intelligence, border and customs agents – plus armed police in schools – as tamping down would-be troublemakers. The commanders of Fort Bliss, the sprawling Army base and airfield occupying northeast El Paso, also get credit for leaning on soldiers to behave better to the point of military police trolling bars to keep intoxicated GIs out of their cars.

Yet even before that national security panic, El Paso’s crime rate trended downward as Albuquerque’s climbed upward in UCR data dating to the mid 1990s.

So what else is at play in El Paso? Culture, a parochial isolation from the rest of Texas, community policing, and perhaps the criminal underground looking out for itself, according to Dr. Richard Pineda, an associate professor at the University of Texas El Paso.

“The culture of the neighborhoods contributes to safety,” said Pineda, an El Paso native who writes on immigration and heads the Sam Donaldson Center for Communication Studies. “There’s not a neighborhood in El Paso I’d feel uncomfortable in while walking through it.”

El Paso has always been a smuggling gateway dating at least to gunrunners feeding Mexico’s revolutions early in the last century. Now the business is drugs.

“What I remember as a kid is that clearly the narcotics stuff is part of the bedrock of post-war El Paso,” Pineda said. “It was just a thing that wasn’t talked about.”

Today, though, the drug pipelines appear to lead around El Paso to distribution points like Albuquerque while anyone involved locally tries to keep things calm. “If there is money moving through the banking industry, you don’t want to draw scrutiny,” Pineda added.

El Paso has its drug problems: heroin in the barrio, cocaine in moneyed circles and marijuana all over, but it lacks the flood of meth fueling psychotic rages elsewhere, said a beat cop not authorized to speak to the media.

Then there’s the culture of the El Paso Police Department where community policing and a respect for residents generally hold sway. Or, as the beat cop told the ABQ Free Press, “You can’t go around being dicks.”

“It’s tough when your police department isn’t up to par,” added banker Moreno referring to Albuquerque. “We have better community relations here.”

Pineda compares his experience with demonstrations in Detroit and Washington, D.C., where police hostilities escalated tension, to the tone of an El Paso rally on the birthday of labor and civil-rights leader Cesar Chavez. “Even the folks who were sort of the loudest and making the most political noise were respectful to the police and vice versa,” he said.

Which brings us to Albuquerque. While the metro area is afflicted with meth, connections between cops and culture began breaking down decades ago with the police response to issues of the time.

“It came to a head in the late 1960s and ‘70s,” said Dr. Michael Jerome Wolff, visiting assistant professor of political science at the University of New Mexico. “The ultimate effect of that was that poorer people developed a cultural attitude of noncooperation with the police.”

Over the years a toxic cycle developed with police tactics, political rhetoric and sensationalist news media fanning each other’s flames as better-off neighborhoods demanded more protection, Wolff said.

“That creates a general paranoia that turns into a more conservative voting pattern and more reactionary policies by politicians,” Wolff said.

In Albuquerque, the early 1970s saw Vietnam War protesters, Chicano activists and pot-smoking young people on one side and police on the other. National Guardsmen bayoneted protestors and a journalist at UNM in May 1970, and a year later the Roosevelt Park riot erupted.

The riot began, according to police, when the weekend crowd in the park interfered with the arrest of four young people for alcohol offenses. Not really, a witness told The Albuquerque Tribune, saying police tried to arrest two young people after an errant Frisbee accidentally hit a squad car.

News accounts recorded dozens injuries, some from shotgun birdshot police fired into the crowd. After the event, Albuquerque’s police chief equipped every squad car with shotguns. The shooting deaths six months later of two Chicano activists by city, county and state officers staking out an explosives shed at a construction site added to ongoing tension.

Riot police returned to Central Avenue in 2003 heaving tear gas and firing pepper-spray rounds into protestors assailing the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Police deployed again last year, although with more restraint, during protests over the fatal police shootings.

Wolff, whose researches organized criminal violence and government responses to dissent in Latin America, said the shooting of civilians by Albuquerque Police Department officers – 42 with 29 fatalities since January 2010 – only widened the divide. Authorities deemed all but one of the deaths justified as the city has paid out more than $23 million so far to settle civil lawsuits.

During that same time, El Paso logged eight fatal officer-involved shootings, one by an off-duty officer in a traffic altercation, another of a handcuffed suspect, according to online news accounts.

“Where you get an increase in police killings, you get a decrease in residents, poor residents, working with police and a general corrosion of state legitimacy,” Wolff said.

Wolff, who has spent time in Brazil, said he sees a parallel between Albuquerque and Rio de Janeiro, a city of more than six million people. There police swept into drug- and gun-infested slums with a pacification program in advance of the 2014 World Cup with an eye on the 2016 Olympics.

“Some areas did not work as well,” he said. “In some you see dramatic shifts in relations where a good police commander has been able to use community policing to improve relations.

“On a city scale it takes a leader. That suggests it’s possible to improve the situation.”

When the U.S. Department of Justice stepped in last year, it blistered APD over a pattern of civil-rights abuses, “longstanding deficiencies” and a “culture of aggression” that places citizens at risk and alienates communities within the city. The city and feds have agreed on an independent monitor to oversee a consent decree dictating reforms, but a federal judge has yet to approve the deal.

(For more on the problems of New Mexico and the Albuquerque Police Department, see my Reforming the Impossible.)

=========

This story by Bill Diven first appeared in the biweekly ABQ Free Press edition of Feb. 11, 2015, and is published here with light additional editing. On Feb. 20 U.S. District Judge Robert Brack approved the federal monitor chosen to oversee the Department of Justice consent decree governing reform of the Albuquerque Police Department. He did not, however, approve the settlement itself pending a hearing on objections to its contents raised by the Albuquerque Police Officers’ Association, the police union.