Symbols do matter whether it’s the flag of rebellion or the swastika of genocide. Take it from someone who’s been on the losing end of one of those arguments.

History matters as well, and we place our country at risk without consensus on the facts and meanings of our shared experience in all its glory and pain.

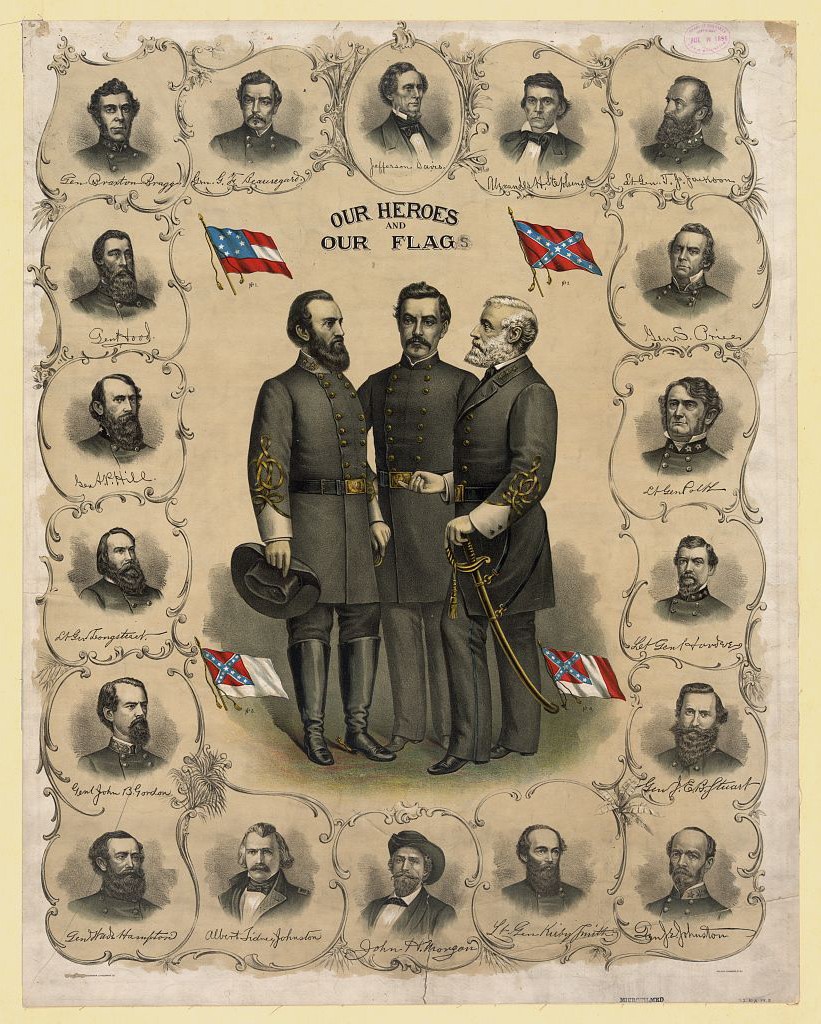

Confederate generals (from left) Stonewall Jackson, P. G.T. Beauregard and Robert E. Lee in “Our heroes and our flags,” Southern Lithograph Company, ca. 1896. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, reproduction number LC-DIG-pga-03338. (Click image to enlarge)

Being conceived in Alabama but born in Illinois doesn’t make me a southerner. Neither does the recent discovery that great-great-great-granddaddy Joseph Diven apparently owned slaves around 1830 in, of all places, west-central Pennsylvania. Still, I must express sympathy for anyone from the Old South defending the Confederate battle flag. For generations their textbooks and public discourse enshrined the Lost Cause with a positive spin on plantation life and its aristocracy while denying slavery as the root of the Civil War.

Yes, we in northern public schools endured our spin, too, like glossing over Abraham Lincoln’s early thoughts on the Constitution protecting slavery. No abolitionist, he initially favored sending slaves back to Africa but evolved into the Great Emancipator with a hopeful vision for the country quashed by his murder.

And while the New South can boast of its own evolution on multiple fronts, denial about its history runs deep and is no accident. Texas downplaying slavery and ignoring Jim Crow in its 11th grade history textbook — “developed just for Texas,” according to its publisher — is only the latest episode in a campaign to inoculate children not against disease but unpleasant truth.

Research by Professor Fred Arthur Bailey, recently retired chair of the history department at Abilene Christian University, found an orchestrated campaign in the late 1800s among Confederate societies and the Southern upper class to sanitize state history textbooks. The effort was aimed as much at restoring the aristocracy to the role of society’s natural leaders over the white underclass as it was obscuring the roots of the Civil War, he wrote.

In reality, (Caroline Brevard) and her fellow southern historians painted truth subjectively, romanticizing the plantation culture, designating slavery as essential for the black race, commiserating with defeated but unconquered Confederate soldiers, condemning northern-sponsored Reconstruction, and hailing those who redeemed the South from Carpetbagger rule. These works presented the aristocrat’s lifestyle as an ideal culture lost forever. … The state histories not only taught race supremacy, but also emphasized the solidarity of whites under patrician leadership. … A well-crafted historical paradigm inoculated children against interpretation dangerous to the aristocratic class. — Bailey, Fred Arthur, The Textbooks of the “Lost Cause”: Censorship and the Creation of Southern State Histories, The Georgia Historical Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Fall 1991), pp. 520, 523, 533.

(In case you haven’t noticed, there’s a new aristocracy believing the country should be run in its image. Their minions spread fear, distrust and circuses masquerading as news until we the people, instead of raging against the machine, rage against each other. So my apologies if this little essay adds to the conflict instead of its resolution.)

Little changed by the time planning for the Civil War centennial began in the late 1950s. Hysteria over communism flourished then, and we changed our national motto from E Pluribus Unum (Out of Many, One) to In God We Trust (take that, you godless unchristian commies). Defenders of segregation doing everything possible to resist change smeared civil-rights activists, notably Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as communists in hopes of subjugating African-Americans forever.

The United States Civil War Centennial Commission appointed by President Eisenhower naively tried to dodge current events and the underlying causes of the war by focusing on unity, valor and mutual respect. Instead of national reflection and fellowship, however, the effort collided head-on with selective memory wrapped in state-sanctioned racism.

In South Carolina, where the cannonading of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor launched the four-year bloodbath in April 1861, public discourse stumbled immediately over what to call the war. The state centennial commission rejected “Civil War” since it implied the South was a rebellious part of the U.S. and not a separate, sovereign nation. So it adopted “The American War Between the Confederated States of America, South, and the Federal Union of the United States of America, North,” commonly shortened to “Confederate War.” The South Carolina commission then published “South Carolina Secedes” listing centennial events including costumed pageants and military reenactments.

Although the program of proposed events reflected the national commission’s goals of peace and harmony, the booklet’s introduction did not, and effectively established the Commission’s official historical interpretation of the War’s cause and meaning. One of the central causes of the conflict, in its view, was “the encroachment of the federal government upon the rights reserved under the United States Constitution.” Slavery was also mentioned, “since abolitionists were disregarding the personal property rights of the citizens of the slave holding states.” — Allen, Kevin, The Second Battle of Fort Sumter: The Debate of the Politics of Race and Historical Memory at the Opening of America’s Civil War Centennial, 1961, The Public Historian, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Spring 2011), p. 99,

Things slid further downhill when the national commission picked Charleston for the centennial kickoff in April 1961. Their black members of other states’ commissions would be denied access to event headquarters, the whites-only Marion Hotel. At the same time, South Carolina raised the Confederate battle flag known as the Southern Cross — actually a rectangular version of the battle flag of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia — over the state capitol in Columbia. Resistance to equal rights for black citizens tainted the celebration, nowhere more clearly than in a speech by Sen. Strom Thurmond, D-S.C.

Thurmond warned the crowd that integration was a Communist plot designed to weaken America. “It has been revealed time and time again that advocacy by Communists of social equality among diverse races… is the surest method for the destruction of free governments. I am proud of the job that South Carolina is doing [in regard to segregation],” Thurmond said, “and I urge that we continue in this great tradition no matter how much outside agitation may be brought to bear on our people and our state.” — Sen. Strom Thurmond speaking at the Marion Hotel, April 11, 1961, quoted in The Day the Flag Went Up.

(Late in life Thurmond soften his views a little without renouncing his earlier actions. After his death in 2003, it was revealed he’d fathered a mixed-race child by a 16-year-old family servant when he was 22.)

The Southern Cross stood atop the statehouse until July 2000 when it was hoisted next to a Confederate memorial on the capitol grounds. There it waved by law at full staff even as other flags were lowered to half-staff after a gunman, allegedly a 21-year-old South Carolinian seething white supremacy, slaughtered nine members Charleston’s Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church during a prayer service six weeks ago. Within a month of the massacre, local and national outrage pressured the legislature into relegating the flag to a museum.

Since then fans of the battle flag waved it at President Obama in Oklahoma, left several on the grounds of Dr. King’s Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and paraded it around numerous places including Carlsbad, N.M., there in the name of “heritage, not hate” and as a representation of Christian values, according to organizers. The national Confederate flag, known as the Stars and Bars, is the actual symbol of slavery, one organizer said.

In Albuquerque Mayor Richard J. Berry, after a local protest and a meeting with African-American leaders, this week announced via Twitter the Stars and Bars would no longer fly over the Old Town plaza beside the flags of Spain, Mexico and the U.S. While he didn’t say so, his decision tacitly rejects the concept of the Confederacy as a sovereign nation when it occupied New Mexico.

Debate continues over what to do about historical plaques and replicas of mountain howitzers the rebels buried near the plaza as they abandoned Albuquerque. Fine and dandy; let’s talk. Don’t forget, though, that there’s real history filled with real people here to be studied and respected, not erased in some sanitation campaign.

New Mexico? you wonder. Well, gather ’round, children. We were the western bastion of the Confederacy complete with battlefields, abuses of Union sympathizers and later disruptions by the Ku Klux Klan and “separate but equal” schools in Carlsbad and elsewhere. The Klan was so comfortable a neon cross lit up its meeting hall in Roswell in the 1920s, and the KKK is believed to be active here today along with other hate groups.

Even before the Civil War we sided with the South endorsing slavery although that is not as simple as it may seem. Yes, we did have slaves, Military officers stationed here had black servants, Hispanics and Native Americans held each other as working captives, and warfare between tribes predating the Spanish conquest produced slave labor as well.

Regardless, New Mexico politics is nothing if not twisted, and the territorial politicians so adept at manipulating Washington and currying favor there weren’t as concerned about slavery as they were about power and profit. In the 1850s Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, soon to be president of the Confederacy, presided over Army surveyors plotting four railroad routes to the Pacific, one through southern New Mexico. Our políticos wanted to make sure that was the one built. But after the South seceded and war began, Lincoln had the votes to pass the Pacific Railroad Act settling on a northern route for the first transcontinental railroad.

Meanwhile a rebel army from Texas marching through El Paso invaded New Mexico in the summer of 1861 heading for the mining riches of Colorado and the eventual taking of California. They captured the badly, perhaps treasonably, led Union garrison fleeing Fort Fillmore and established nearby Mesilla as the Confederate capital of Arizona. From there they marched up the Rio Grande chasing federals back into Fort Craig during the Battle of Valverde and occupying Albuquerque and Santa Fe. The rebels defeated New Mexico and Colorado troops at the Battle of Glorieta Pass but lost their wagon train and supplies in the process forcing a slow and painful retreat back to Texas.

In a recent letter to the editor of the Albuquerque Journal, the writer complained flying the Stars and Bars over Old Town wasn’t justified by the six-weeks the rebels occupied the town. Actually the Confederates and their many sympathizers ran wild in New Mexico for more like a year and would have dug in and stayed longer had not Colorado sent militia from the north while California sent a column from the west to chase the rebels out of what is now southern Arizona.

You can argue over whether the Stars and Bars or the Southern Cross is the flag of slavery, but at this point in history that doesn’t matter much. It was Lee’s battle flag defenders of racial segregation adopted as their banner 100 years after the war forever confusing any residual honor from the Lost Cause with white supremacy. To claim it as strictly a symbol of your heritage is to walk a very thin line especially if your great-granddaddy didn’t fight under General Lee.

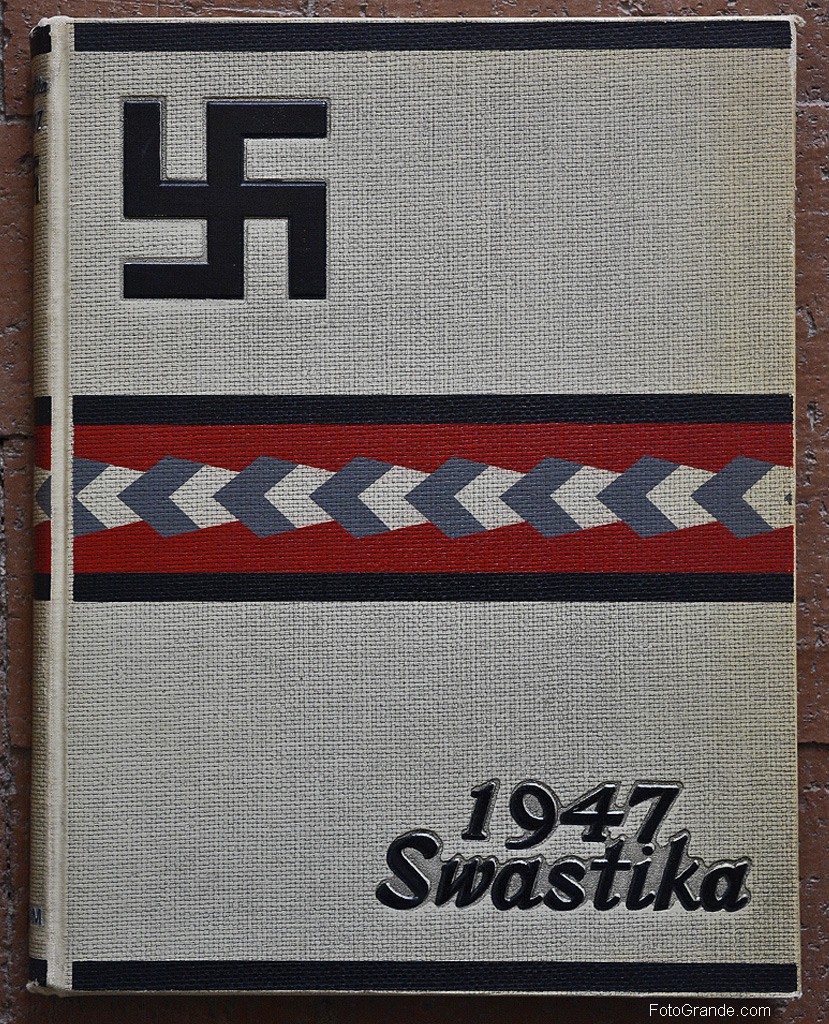

Which brings me around to the swastika, the emblem hijacked by Adoph Hitler as a symbol of Aryan pride and linked in perpetuity with the atrocities of his Nazi Germany and the industrial-scale murder of six million Jews. To display a swastika outside an honest historical context today only invites trouble.

Ceiling motifs in the 1923 Schaffer Hotel, Mountainair, N.M. Photo © William P. Diven. (Click image to enalrge)

When my family arrived in New Mexico fewer than 20 years after the end of World War II, we found prewar swastikas built into an Albuquerque federal building and other public and private structures but no longer the brand name for a coal company and its Swastika Route railroad. Surprisingly, to us, New Mexico State University, where Dad was a graduate student, still called its yearbook the Swastika as it had since 1907. Chosen by students in a naming contest, “swastika” was picked as a Native American symbol for fortune and good luck whose roots trace back millennia in multiple cultures and religions. (See: How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it)

The name held during the war years at what was then A&M — the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanical Arts — as about 2,000 Aggies took up arms with at least 125 dying during the war and many more scarred physically or emotionally. There was debate about the yearbook name, but it survived as something “quite native rather than something pro-Hitlerite,” Dr. Simon Kropp wrote in “That All May Learn,” his history of NMSU. The symbol returned to the cover in the second school year after the war ended, 1946-47, and the name lasted into the 1980s when complaints by a later generation led to its demise.

I favored keeping the name as a triumph of history over evil but understood its offensive side, especially if the Nazis gassed your relatives or your aunt displayed a number tattooed on her forearm, as did one of my childhood neighbors. So I’m OK with relegating the Swastika to bookshelves and the NMSU Archives while remembering its better times. Call it a show of respect by not waving a symbol of genocide in the face of people to whom it represents personal or cultural tragedy on a mass scale.

The same must be said of the Confederate battle flag. The story of Lee and his army is a significant piece of who we are as a country, and the debate over the battle flag should not shame the men enlisted to fight and die under its colors. Neither is the Confederacy in the same league as the Nazi horrors. Yet that flag suffers the same fate as the swastika, perverted by a powerful few in the name of racial superiority. Waving it wantonly simply delays the healing needed for our collective future.

I greatly enjoyed your commentary. Thank you. There is one fact I would like to see mentioned more often in discussion of the causes of the Civil War. It is NOT relevant to the flag controversy, to slavery, or current attitudes and for that reason might not have been right for this piece, but its validity is often discounted because of its misuse by apologists for the Confederacy.

I refer to the issue of States’ Rights or the question of federalism vs. the concept of a confederation of independent and equal states. The latter was intended by many of the founding fathers and is articulated in many early American documents. Henry Clay was perhaps the most vocal advocate. President Andrew Jackson’s moves to make the Presidency more powerful was probably the beginning the abandonment of the States’ Rights concept and the centering of power in Washington DC. While the popular view now is that States’ Rights is a canard used to hide evil intent re. slavery, many non-slaveholders in the South, including Robert E Lee believed in the concept and felt that no state had the right to dictate to another and that any state had the constitutional right to secede from the Union. Whether they were right and whether that idea carried any moral weight when stacked up against the issue of slavery is of course another matter.