Let us marvel at what happens when a savvy citizen with strong views on the Constitution and border protection bumps head first into the reality of southern New Mexico.

Witness the tale of Tim Blomquist, insurance agency owner, former Army intelligence officer, and a stranger in this strange land.

Blomquist told Albuquerque Journal columnist Leslie Linthicum he’d never seen a Border Patrol roadblock until he blissfully blew by one on Interstate 25 thinking it was some kind of truck inspection. (Her column here.)

“In all of my 54 years, I have never had anybody question my citizenship or demand my citizenship status. Keep in mind, I’m an American citizen, and I’m in the heartland of this country.”

For a man of 54, Blomquist needs to get out more.

Blomquist is from Farmington in far northwestern New Mexico, which does have its own international borders. But so far the Navajo, Ute and Jicarilla nations aren’t confronting travelers with armed agents asking about citizenship and sniffing for drugs. So Blomquist’s motorcycle trip into southern New Mexico is a good start to confronting daily life in a Twilight Zone.

After spending Independence Day night in Las Cruces, Blomquist rode into trouble heading toward home on I-25. Shortly after leaving Las Cruces he split the highway cones on his Triumph and skipped the exit lane to immigration inspection. He waved a friendly wave back at the feds waving franticly at him and was rewarded with a short pursuit and roadside interrogation (“I’m confused. Did I cross into Mexico?”).

Then it was an hour in the office being questioned further, fingerprinted and released without charges but with a recommendation to stop at Sparky’s burger and barbecue joint in Hatch (it was closed).

What seemed to upset Blomquist, though, was not the interrogation and all that, which he described as being quite civil except for one agent who insisted on yelling a lot. Instead it was two profound revelations:

- A citizen’s constitutional right to move freely about the country ends when you venture within 100 miles of the border; and

- Being called the Border Patrol doesn’t mean you patrol the actual border. (“What the hell are you people doing up here? Why aren’t you down on the border?”)

For starters he’s misinformed calling the county of Doña Ana the heartland when it’s part of la frontera, the international frontier special to both sides of the border with it’s own customs and laws. Here the map line becomes a broad stripe.

No border: Only rivers and mountains crossed this country — and then, as now, the lay of the terrain and the flow of the water was north and south. No line running east to west. The land here was inseparably one. — Alan Weisman, La Frontera: The United States Border with Mexico, (Photographs by Jay Dusard), Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, New York, 1986, p. 122.

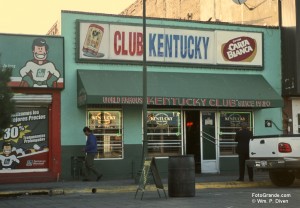

For those of us who grew up on the U.S. side of la frontera, we discovered long ago it was easier to leave the country than the county. And it still was last time I visited Cíudad Juárez on business and for a cuba libre at the Kentucky Club, a famous relic from Prohibition when U.S. citizens simply walked across the bridge from El Paso to enjoy a legal drink (not that they couldn’t find an illegal one at home). Mexican border officers cared a lot less about me than la migra does on state and U.S. highways.

It’s been 45 years or so since the Border Patrol began diverting traffic off I-25 to interrogate travelers and make warrantless searches at Truth or Consequences in Sierra, the next county north. By law and policy at the time, the feds exercised those special powers within 100 miles of the border, and the Border Patrol measured the T or C roadblock at 98 air miles from Mexico.

When agents began hunting for undocumented foreigners in glove boxes and came up with marijuana arrests, a federal appeals court overturned criminal convictions, at least until the Supreme Court took a look. In 1976 the Supremes ruled T or C and similar stationary checkpoints to be an extension of the border where your broader rights protecting you from police interrogation and unreasonable search and seizure don’t apply.

Some years later the feds decided to stop giving that first 100 miles away for free to smugglers, mules and indocumentados. Now the first I-25 checkpoint is only about 55 miles from the border and 15 miles north of Las Cruces. The T or C checkpoint rarely opens these days and appears to be mostly a parking lot for a million or two dollars in Border Patrol cars and trucks bought, presumably, with some purpose in mind.

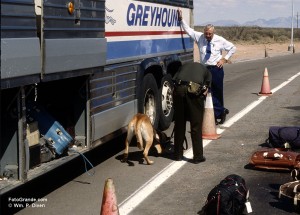

For the first-time traveler, it’s intimidating to be forced unexpectedly off a public highway, confronted by red lights and a stop sign and then undergo questioning by an armed officer in a dark-green uniform while another agent walks around with an anxious K-9. For locals it’s just another day en la frontera rarely rising to the level of nuisance unless traffic is backed up and stalled and if you ignore the civil-rights issue.

If you’re a gringo and look local a simple “yes” usually ends the citizenship quiz, and you’re back on your way. My personal contest is to slip through without actually coming to a complete stop, although that’s harder these days.

If something sparks the agent’s curiosity, as it did when I rolled into the I-10 checkpoint driving one of the first Jeep Wranglers in the area, it was time to play a seemingly casual game of 20 Questions: Nice car ya got there. What year is it? Cool. What size engine does it have? Stumble with an answer and, uh oh, you’re pulled aside for detailed inspection.

Traveling in a cross-country bus doesn’t avoid the citizenship question and can be troublesome if, say, you’re an aged black man and the federal dog alerts to the prescription meds in your suitcase down below. You’ll find your luggage on the pavement as you’re hauled out to explain yourself.

And looking local may actually work against you. Some years ago a many-generation local named Chávez traveling with our group was singled out for aggressive questioning at T or C while we four white guys were all but ignored. Only his complexion made him suspicious.

Got a green card or a tourist visa? If you’re papers are in order, probably no sweat. If not, and even if you’re legal, you’re in for a hassle.

And carrying drugs? Take your chances if you want, especially if you’re traveling with prescription marijuana. You likely won’t go to jail if you’ve got a marijuana card, but you won’t see your pot again, either.

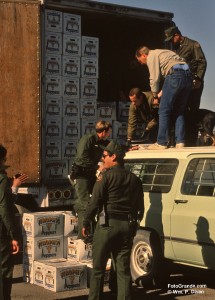

Oh, and those random big busts? You know, the truck driver who acted nervously so they searched his trailer? You don’t hear about those as often these days as the contrabandistas have their own tricks to stay ahead of the federales and their locked-down concrete-and-steel outposts.

In the 1960s, this game was called Feds and Heads.

For that matter, I’m not sure about the actual randomness of those seizures. In a federal drug trial I covered an agent testified they knew the load was leaving El Paso, but because the court there was so overloaded, they let it go into New Mexico and sent an alert ahead.

“I’m just an old-fashion conservative,” Blomquist told me in one of the many calls he took after Leslie’s column came out. And that’s what you get, a soft-spoken, civil and broadly knowledgeable business person and veteran concerned about civil rights and respectful of opposing views when expressed with equal respect.

He said he worked in one of Ronald Reagan’s campaigns, even had lunch with the Gipper, and cites the relationship between Republican Reagan and Tip O’Neill, the Democratic speaker of the House, as how Washington should run fighting your battles honestly during the day and talking and compromising as colleagues in the evening.

However, his Border Patrol encounter far from the real border coupled with the venomous political expression he’s encountered in recent years worries him.

“This is America. We don’t do that,” he said. “I’m really concerned about where our country is headed.”

Meanwhile life in la frontera goes as it has ever since someone tossed a map line like a badly thrown rope from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean. So, welcome to the other world, Mr. Blomquist, where you’re a foreigner in your own land.

Nice one Bill!

We still more statesmanship than gamesmanship around border patrol issues and other public policies, but I imagine that Number 45 is a sloppy, mean bigot, so rule out cocktail hour.